Mastering Rotational Dynamics: The Moment of Inertia of the Cylinder Explained

Mastering Rotational Dynamics: The Moment of Inertia of the Cylinder Explained

The moment of inertia of a cylinder lies at the core of rotational physics—governing how objects spin, balance, and resist changes in angular motion. For engineers, physicists, and designers alike, understanding this fundamental property is essential for applications ranging from mechanical systems and prosthetics to spacecraft stabilization and kinetic art installations. The cylinder, a ubiquitous shape in both nature and industry, presents a well-defined and analytically tractable model for calculating angular resistance, making it a cornerstone in rotational mechanics.

At its essence, moment of inertia quantifies an object’s resistance to angular acceleration, dependent not only on mass but critically on how mass is distributed relative to the axis of rotation. For a solid cylinder rotating about its central longitudinal axis, this distribution follows a predictable geometric pattern: mass concentrated along the axis. This specific geometry enables precise mathematical treatment—unlike irregular shapes, where complexity grows rapidly.

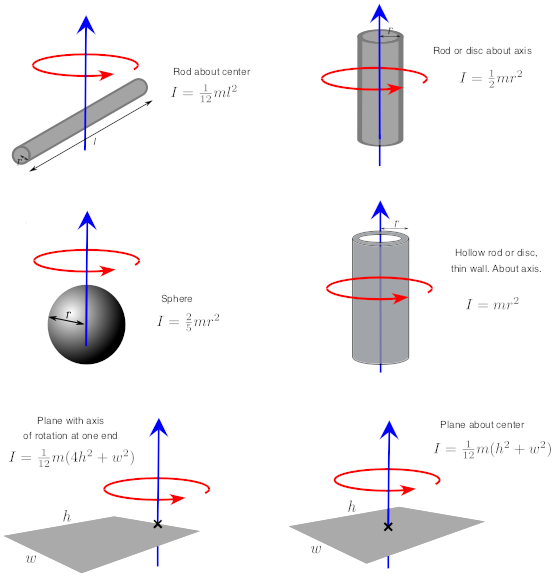

The moment of inertia of a solid cylinder is defined as I = (1/2)mr², where m is mass, r the radius, and the factor 1/2 reflects the radial spread of mass.

This formula—derived from integration over cylindrical volume elements—reveals deeper insights. Since all mass lies at a constant distance r from the axis, the moment of inertia increases quadratically with radius, emphasizing why larger diameter cylinders resist angular changes far more than larger solid masses would suggest. In technical terms, the value r² dominates rotational inertia; doubling the radius quadruples the moment of inertia.

"For a cylinder, every millimeter of radius significantly amplifies resistance to rotation," explains Dr. Elena Torres, applied mechanics researcher at the Institute of Dynamic Systems. "That’s why supporting casters on weights must be carefully counterbalanced—mass placed far from the axis increases inertia disproportionately."

In real-world applications, the cylinder’s moment of inertia directly impacts dynamic performance.

In mechanical design, engineers use I to optimize gears, shafts, and flywheels. A flywheel designed to store rotational energy must balance high moment of inertia with material strength; too massive a cylinder increases inertia but may exceed load limits. Likewise, in electric motors driving precision robotics, minimizing moment of inertia through tapered or hollow designs allows faster, more responsive movements by reducing angular resistance.

The cylinder’s symmetry further simplifies analysis.

Its identical rotational properties about the central axis eliminate the need for vector components under standard conditions. This symmetry, combined with predictable stress distribution, makes the cylinder ideal for systems requiring consistent angular momentum, such as flywheel energy storage units or flywheel gyroscopes used in stabilizing spacecraft. As physicist Marcus Chen notes, “The cylinder is nature’s optimized shape for inertia—distributing mass efficiently to maximize resistance while minimizing wasted space.”

While solid cylinders dominate standard inertia models, variations exist.

Hollow cylinders, with inner and outer radii, alter the moment of inertia per unit mass. For a hollow cylinder, the expression becomes I = (1/2)m[(r₁² + r₂²)/2], where r₁ and r₂ are inner and outer radii. This subtlety matters in precision engineering—designers must account for wall thickness when predicting rotational response.

“Ignoring wall stiffness and material distribution can lead to unexpected vibrations or instability,” warns aerospace engineer Fatima Ndiaye.

Different axes of rotation introduce variation. Rotating about an end rather than the central axis changes the moment of inertia dramatically. For axial rotation, I = (1/2)mr² holds; for rotation about a tangent point, a geometric factor emerges via the parallel axis theorem: I = I_cm + md², where I_cm is the inertia about the center, and d the distance to the new axis.

“Calculating the moment of inertia for non-standard axes is not trivial—it demands careful integration or numerical methods,” says computational physicist Raj Patel. “Yet the cylinder’s regular geometry ensures even these exceptions remain tractable.”

Applications span disciplines. In biomechanics, human limbs modeled as composite cylinders help predict rotational motion during athletic maneuvers.

In manufacturing, rotating drums and conveyor rollers rely on accurate inertia values to synchronize with motors. Even in consumer products—uch, rotating game pieces, puzzle disks, or folk instruments—designers exploit the cylinder’s predictable inertia to balance durability and responsiveness. “Moment of inertia isn’t just a number—it’s the silent controller of motion,” observes mechanical engineer Lucia Moreau.

“Without understanding it, even the most powerful motors can stumble."

The moment of inertia of a cylinder exemplifies how elegant physics underpins everyday mechanics. From micro-engineering to macro-structure, this shape’s rotational fingerprint guides innovation. As both a theoretical benchmark and a practical planning tool, the cylinder’s inertia remains a litmus test for efficiency, control, and design precision—a testament to the power of fundamental principles in shaping technology, one rotation at a time.

Related Post

The Boiling Point of Water in Kelvin: A Scientific Benchmark Defining Thermodynamics

What Is Rugby? A Simple Explanation of the World’s Eigen Sport

Phil Wills’ Craft: The Rise of The Mixology Maestros Through The Bar Rescue Biography

Snow Rider GitHub: Unleashing the Power of High-Performance Snowmobile Image Recognition