BacterialColoniesOnAPetriDish: The Hidden Microscopic World Revealed

BacterialColoniesOnAPetriDish: The Hidden Microscopic World Revealed

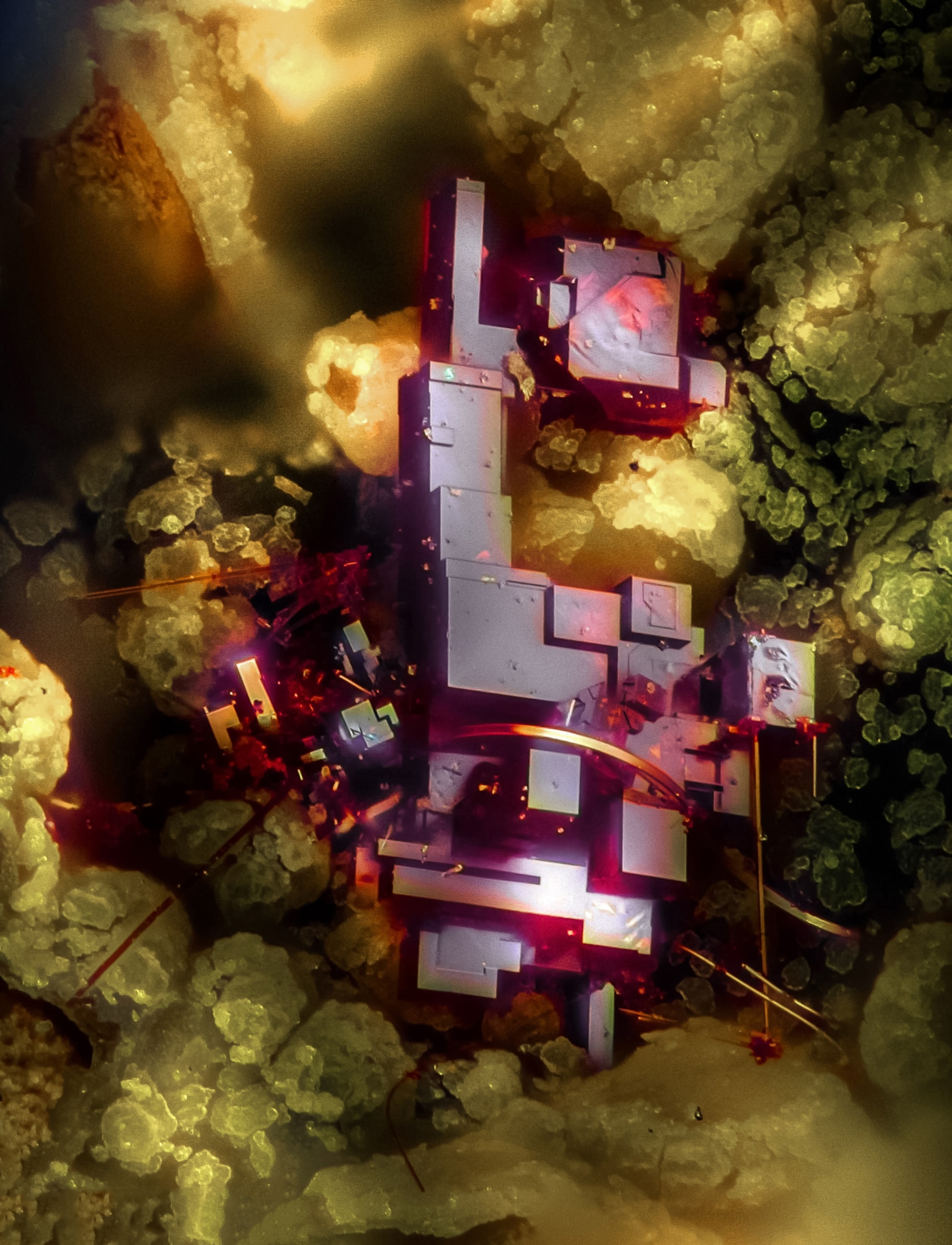

When viewed under the lens of a microscope, a simple bacterial culture grown on a petri dish becomes far more than a blurry cluster of cells—it transforms into a firsthand window into microbial diversity, growth dynamics, and biological complexity. A bacterial colony on a petri dish is the visible manifestation of microbial life, shaped by intricate interactions between microorganisms, nutrients, and environmental conditions. From medical diagnostics to environmental monitoring, these visible colonies offer critical insights into bacterial behavior, pathogenicity, and innovation in laboratory science.

Every drop of liquid inoculated onto agar transforms into a tangible timeline of biological processes. Within hours, tiny swirls of growth expand into structured colonies, each colony representing a single ancestral cell or group of closely related organisms. These colonies are not random; their size, shape, color, and margin distinguish different bacterial species and strains.

“A single colony can be the fingerprint of a specific bacterial lineage,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, microbiologist at the National Organization for Medical Research. “By analyzing these microcolonies, scientists decode the invisible rules of microbial ecology.”

The formation of bacterial colonies begins when a scientist spreads a diluted bacterial suspension across the surface of nutrient-rich agar.

The agar, typically supplemented with glucose, peptone, and antibiotics, supports specific growth while filtering out non-target microbes. Bacteria multiply via binary fission, spreading radially from the inoculation point. As they consume nutrients and release waste, they create distinct colonies marked by density, diameter, and structural features—characteristics that enable laboratory identification.

Each bacterial colony is a microscale ecosystem. Factors such as temperature, pH, moisture, and oxygen levels directly influence colony morphology. For instance, fastidious bacteria like *Staphylococcus epidermidis*, commonly found on skin surfaces, thrive in nutrient-limited conditions and form small, translucent colonies within 24 to 48 hours.

In contrast, rapidly growing pathogens like *Escherichia coli* form darker, raised colonies within 18 to 36 hours at optimum temperatures around 37°C. “Environment dictates behavior,” notes Dr. Marcus Lin, a specialist in bacterial phenotyping.

“A colony’s appearance tells a story of adaptation.”

Colonies vary widely in texture and appearance—some are smooth and shiny, others porous or elevated with a rough edge. Pigmentation plays a distinguishing role: countries like *Bacillus subtilis* develop golden-yellow colonies due to carotenoid production, while *Proteus mirabilis* produces greenish colonies influenced by urease activity. These visual cues serve as early diagnostic markers, guiding microbiologists toward targeted identification and antimicrobial sensitivity testing.

Colony morphology also reveals genetic differences. Parent bacteria may harbor mutations or plasmids that alter metabolic pathways, antibiotic resistance genes, or toxin production. By studying these variations, scientists trace evolutionary pathways and monitor emerging strains, especially concerning antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.” In clinical labs, bacterial colonies on petri dishes form the foundation of diagnostic workflows, enabling rapid identification of infections with minimal equipment.

Beyond the lab, petri dish colonies inspire innovation in biotechnology, sustainability, and education. In environmental science, soil and water samples cultured on agar pinpoint microbial indicators of contamination or ecosystem health. In bioremediation, certain bacterial colonies degrade pollutants, offering green solutions to industrial waste.

Meanwhile, bacteriologists use colonies as teaching tools, demonstrating microbial growth stages and colony morphology to students worldwide. The technique’s simplicity belies its power. A basic setup—a petri dish, agar medium, inoculating loop, and incubation chamber—conceals profound scientific potential.

Every visible colony is an opportunity: to diagnose disease, study evolution, or unlock nature’s hidden biochemical factories. “Watching bacterial colonies unfold reveals life at its most elemental,” says Dr. Torres.

“Each one is a tiny universe, packed with possibility.” From medical research to ecological monitoring, bacterial colonies on petri dishes serve as both diagnostic tools and living records of microbial adaptation. Their growth patterns, colors, and structures provide essential data that bridge everyday observation and cutting-edge science. As technology advances, imaging methods like automated colony recognition and machine learning analysis are transforming how colonies are studied—yet the fundamental lesson remains unchanged: beneath the microscope lies a microscopic world rich with complexity, waiting to be seen, studied, and understood.

Related Post

Emma Cannon: Everything You Need to Know About Her Life and Career

American Crocodiles in California: A Rare, Prehistoric Presence Along the West Coast

Boeing 777 Crash in Dubai: What Really Unfolded at DXB’s Runway in 2023

Snake River Roasting: Elevating Coffee with Precision From Idaho’s High-Altitude Beans