Why Cystic Fibrosis Isn’t Just Dominant – Here’s the Genetic Truth

Why Cystic Fibrosis Isn’t Just Dominant – Here’s the Genetic Truth

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is widely perceived as a recessive disorder, but the genetic reality is more nuanced — determined by a complex interplay of inheritance patterns, gene expression, and clinical variability. While CF is primarily inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, emerging insights reveal limitations in simplistically labeling it as such, highlighting the role of co-dominant elements, modifier genes, and environmental influences in its expression. Understanding whether cystic fibrosis is truly recessive requires unpacking the biology, inheritance models, and clinical nuances behind this life-altering condition.

The foundation of cystic fibrosis lies in mutations of the CFTR gene. This gene, located on chromosome 7, encodes the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein, essential for regulating salt and water transport in epithelial cells. Caused primarily by defects in this single gene, CF’s inheritance pattern is often assumed to be recessive—where both parents carry a mutated CFTR allele and pass one to their child—resulting in disease manifestation. But the story begins with how these genes interact at the molecular level.

Autosomal Recessive Inheritance: The Traditional View

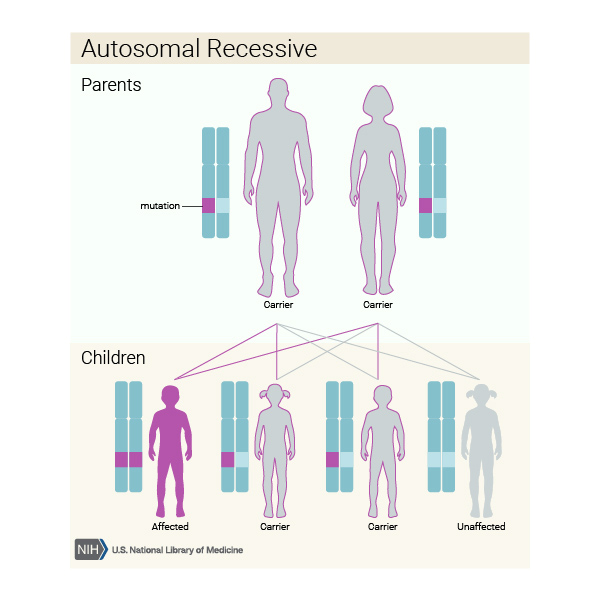

For decades, cystic fibrosis has been taught as a textbook example of autosomal recessive inheritance.This model requires an individual to inherit two defective copies of the CFTR gene—one from each parent—for the disease to develop. If only one copy is inherited, carriers remain symptom-free but can pass the mutation to offspring. Statistically, two carrier parents have a 25% chance of having an affected child, often viewing this as a clear-cut inheritance pattern.

- Example: If both parents are phenotypically normal carriers (heterozygous), each child has: - 25% probability of being affected (two recessive alleles) - 50% probability of being a carrier - 25% probability of being unaffected and non-carrier This pattern supports the classification as recessive—yet real-world Genetics reveals exceptions that challenge simplicity.Beyond Two Mutant Alleles: The Role of Modifier Genes and Epistasis

While two defective CFTR alleles are necessary for full phenotypic expression, they are not invariably sufficient. Scientists increasingly recognize that other genes—known as modifier genes—influence how the primary CFTR mutation manifests. These genetic “helpers” or “blockers” can amplify or dampen disease severity, sometimes allowing carriers or even heterozygous individuals to display subtle symptoms. Research indicates that variations in genes involved in inflammation, inflammation response, and mucus production alter clinical outcomes.For instance, polymorphisms in the *ATP13A2* or *GBA* genes may modify lung disease progression in CF patients despite identical CFTR mutations. This variability suggests that CF’s expression is not strictly recessive but shaped by a network of genetic interactions. This cumulative effect diminishes the strict binary view of inheritance.

“It’s not just about having the mutated gene,” explains Dr. Elena Darmon, a geneticist specializing in respiratory disorders. “The surrounding genetic context can either intensify or mitigate the disease’s impact—making the inheritance model more complex than a simple dominant-recessive illusion.”

Carrier Screening and Real-Life Inheritance Dynamics

In clinical practice, screening for CFTR mutations plays a vital role in reproductive planning.Preconception or prenatal carrier testing identifies individuals who may pass on recessive CFTR mutations. However, even when both parents are carriers, only 25% of children integrate two defective alleles. Yet, the possibility of rare cases—such as compound heterozygosity (mutations at two distinct sites on the same CFTR allele) or digenic inheritance—points toward rarer, less predictable patterns.

Compound heterozygosity, while still following recessive logic, adds complexity: one parent may contribute a rare mutation not seen in common carrier panels, complicating genetic prediction. Such cases remain uncommon but remind clinicians that the inheritance landscape is not uniformly recessive but genetically heterogeneous. Additionally, de novo mutations—new mutations not inherited—occur in about 10–20% of CF cases

Related Post

Jc Monahan Nbc Boston Bio: Mandela of Boston’s Public Scene, Husband of a Rising Star in Media

Les Raisons Pour lesquelles eBay Français Domine le Marché de la Vente En Ligne

Unveiling The World of Sharpe: A Deep Dive into the TV Series That Redefined Military Drama

Illuminating the Invisible: Inside the Interface of Innovation and Intelligence in Science