What Are Possessions? Definition and Everyday Examples That Shape Our Lives

What Are Possessions? Definition and Everyday Examples That Shape Our Lives

Possessions define the quiet space between individuals and the material world—objects we own, use, or cherish that form invisible threads in the tapestry of daily life. At their core, possessions are physical items. Yet their significance runs far deeper, touching psychology, economics, culture, and identity.

From the locket passed through generations to the smartphone that connects us instantly, possessions are far more than mere belongings; they are functional tools, emotional anchors, and cultural markers. Understanding what constitutes a possession reveals how humans select, value, and integrate objects into their lives. This article explores the precise definition of possessions, examines real-world examples across contexts, and reveals why these items matter more than we often acknowledge.

Defining Possessions: More Than Just Physical Objects

What Are Possessions? A possession is any physical object intentionally owned, controlled, or occupied by an individual—whether temporarily or permanently. More than just ownership, possessions represent a human interaction with material culture that transcends ownership itself. While some possessions are acquired through purchase, inheritance, or gift, many carry symbolic weight that elevates them beyond mere utility.Economists classify possessions as fixed assets, distinguishable from transient items, emphasizing their long-term role in personal and societal structures. Possessions are not solely defined by price or permanence. - They can be tangible—rulers, clothing, cars— - Or intangible in form, such as digital files, cloud storage access, or subscriptions.

Psychologically, possessions function as extensions of self—what sociologist Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption”—but also as practical supports that enable daily functioning. In legal terms, possession grants control over an item, even if ownership is not legally transferred, highlighting a functional and relational dimension. Classifying Possessions Possessions fall into broad categories based on function and emotional resonance:

- Essential Possessions: Everyday items critical to survival and routine, such as clothing, medication, and housing.

Without these, basic needs cannot be met.

- Comfort and Utility Possessions: Objects that enhance well-being, from kitchen appliances and tools to ergonomic furniture and fast-charging devices.

- Sentimental Possessions: Items carrying emotional or symbolic value—family heirlooms, gifts from loved ones, childhood toys, or keepsakes tied to pivotal life moments.

- Investment Pieces: Assets valued for appreciation, including real estate, art, collectibles, and luxury goods, often serving dual purposes: personal enjoyment and financial security.

Examples of possessions illustrate this multidimensional role. A workplace staples kit—glasses, a laptop, notepads—supports career function.

A grandmother’s recipe journal, though rarely seen, anchors family traditions. Luxury watches or designer bags may serve status and comfort, while a cryptocurrency wallet holds digital wealth with profound economic implications. Even digital possessions—e-books, music libraries, online accounts—represent modern incarnations of ownership, reflecting evolving definitions of what one can “possess.”

Consider the smartphone: a linchpin of contemporary life.

Used for communication, navigation, entertainment, and productivity, it combines utility, emotional attachment, and social identity. Its surrender or loss often triggers distress, illustrating how possession extends beyond the object itself to the relationship it sustains. Similarly, a college diploma—secured through study—serves both practical employment access and symbolic self-worth, embodying both tangible and emotive value.

In economic systems, possessions drive exchange, substitution, and inequality. Ownership patterns influence wealth distribution, with access to lasting possessions often determining life trajectory. Sociologists note that possession habits reflect cultural values—what a society deems worthy of keeping shapes collective priorities.

In personal life, possessions reduce uncertainty, offer continuity, and provide a sense of agency in an unpredictable world. Ultimately, possessions are silent participants in human experience. They are not only things we own, but keys to understanding how people relate to time, memory, identity, and community.

Their definition—rooted in ownership, utility, emotion, and meaning—reveals the quiet power objects hold in structuring lives. In every handheld device, inherited heirloom, or digital account, possessions speak of who we are, what we value, and how we matter.

Related Post

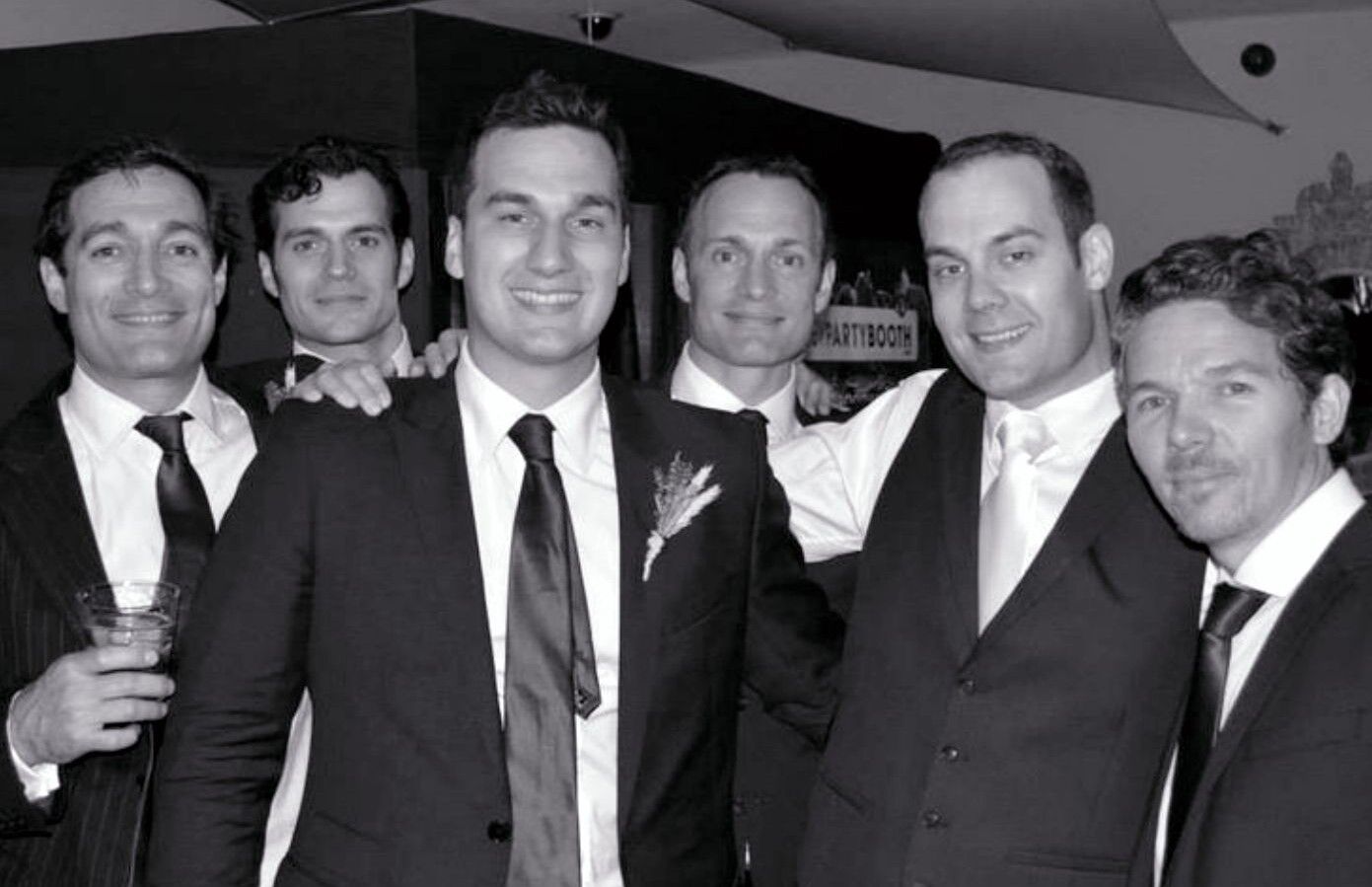

A Closer Look At The Life Of Henry Cavill’s Brother – Beyond the Spotlight, A Family Legacy Forged in Quiet Resilience

Unveiling The Intriguing World Of Lilbabyanthony: A Journey Through His Life And Legacy

Revolution in the Spectrum: How Modern Bands Are Transforming Radio’s Future

Decoding Alert and Oriented X1: The Brainwave signal Shaping Human-Machine Synergy