Unlocking Molecular Precision: The Critical Role of Trigonal Pyramidal Bond Angles

Unlocking Molecular Precision: The Critical Role of Trigonal Pyramidal Bond Angles

At the heart of molecular geometry lies a microscopic yet profound determinant of chemical behavior—angular precision. The trigonal pyramidal bond angle, a defining feature of molecules like ammonia (NH₃), ammonium (NH₄⁺), and certain nitrogen-containing biomolecules, governs molecular shape, reactivity, and interaction dynamics. Typical for sp³ hybridized atoms with a lone pair occupying one hybrid orbital, this bond angle—deviating slightly from the ideal 109.5° observed in tetrahedral structures—creates a distinctive three-dimensional profile that enables unique chemical functions.

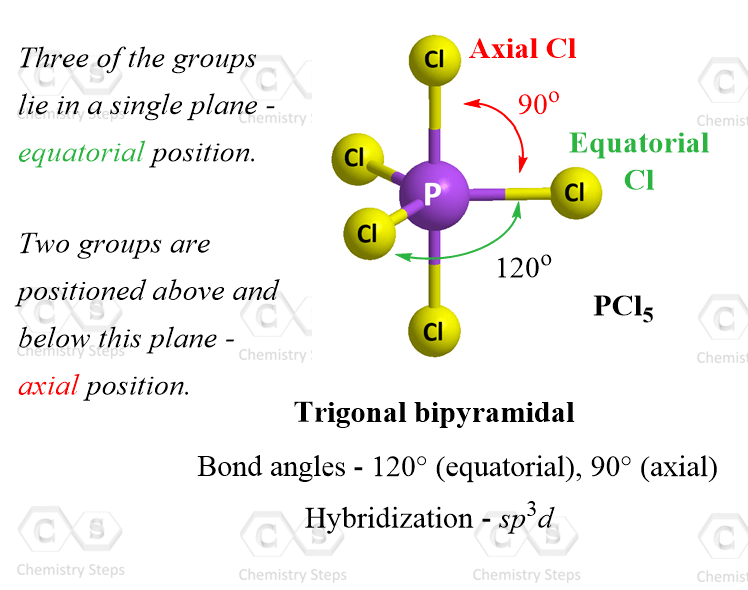

Understanding its values, variations, and implications reveals deep insights into molecular stability and design in chemistry and biology. The foundational understanding begins with molecular geometry rooted in VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) theory, which predicts molecular shapes based on electron pair repulsion. In a trigonal pyramidal arrangement, three bonding pairs surround a central atom while one occupied orbital holds a lone electron pair.

This lone pair exerts stronger repulsive forces than bonding pairs, compressing adjacent bond angles and resulting in a characteristic measure slightly less than the ideal tetrahedral angle of 109.5°.

For ammonia (NH₃), the canonical example, experimental measurements reliably place the H–N–H angle at approximately 107.3°—a value that reflects the compromise between electron repulsion and geometric constraints. This deviation is not arbitrary; it stems directly from the balance between the strong lone pair–bond pair repulsion and the need to minimize overall system energy.

"The lone pair effectively pushes the bonding pairs closer together," explains Dr. Elena Petrova, a physical chemist at MIT specializing in molecular structure. "This angular contraction defines the trigonal pyramidal signature and critically influences ammonia’s basicity and hydrogen bonding capability."

In contrast, the ammonium ion (NH₄⁺)—formed when ammonia gains a proton—exhibits a perfectly symmetric tetrahedral geometry with bond angles of 109.5°.

This shift occurs because the added positive charge removes the lone pair from the central nitrogen, replacing a repulsion-dominated environment with one dominated solely by predictable solo bonding pairs. “The loss of the lone pair eliminates asymmetry and stabilizes the ion through uniform spatial distribution,” notes Dr. Petrova, underscoring how subtle electronic changes profoundly shift molecular geometry.

Trigonal pyramidal bond angles extend beyond NH₃ and NH₄⁺, appearing in complexes involving nitrogen in pharmaceuticals, catalysts, and natural products. In medicinal chemistry, the precise orientation of nitrogen lone pairs and adjacent bonds affects drug-receptor binding, influencing potency and selectivity. Similarly, in industrial catalysts, the angular structure dictates how molecules orient and react on active surfaces, impacting reaction efficiency and yield.

The measured angle, though small in degree, acts as a key parameter in predictive modeling and molecular design.

Quantifying these angles requires precision. Advanced techniques such as X-ray crystallography and neutron diffraction provide atomic-level resolution, reliably capturing bond angles within ±0.5° margin of error.

Spectroscopic methods, including microwave and infrared spectroscopy, complement these measurements by analyzing vibrational modes tied to angular geometry. Together, these tools enable chemists to validate theoretical models and refine structural hypotheses with high confidence.

While the ideal tetrahedral model offers a helpful benchmark, real-world systems rarely conform exactly.

Subtle deviations from the 109.5° norm reveal much about local electronic environments. For instance, electron-withdrawing or donating substituents alter lone pair distribution, shifting bond angles infinitesimally but meaningfully. In strained or bulky molecular frameworks—such as fullerenes or metal-organic frameworks—steric effects further distort angles, demanding contextual analysis.

"No single angle exists in isolation," clarify materials scientists. "It is part of a dynamic interplay between electronic structure, steric demand, and external conditions."

Consider the broader chemical landscape: when nitrogen forms multiple bonds—such as in amines or azides—the bonding geometry adapts. In primary amides or substituted ureas, resonance and delocalization subtly reinforce pyramidal angles, stabilizing specific conformations essential for protein folding and enzyme function.

In agrochemicals and polymers, tailoring bond angles allows engineers to manipulate material properties like polarity, solubility, and thermal stability. Thus, mastery of the trigonal pyramidal bond angle unlocks control over molecular function across scientific frontiers.

In sum, the trigonal pyramidal bond angle embodies a delicate merger of theory and real-world behavior.

Far more than a static number, it reveals the dynamic tension between electron repulsion, molecular symmetry, and environmental influence. As measurements grow increasingly precise and computational models advance, the angle remains a pivotal metric—informing everything from drug discovery to nanomaterials design. By dissecting its nuances, scientists continue to decode the invisible forces shaping chemical reality, one angular degree at a time.

Related Post

The Trigonal Pyramidal Bond Angle: A Quantum Playground of Electron Repulsion

Unlock Secure Authentication with Mythr.Org Log In — Your Gateway to Unmatched Login Efficiency and Security

Holo Stock News Today Unlocks Stocktwits Insights to Decode Market Sentiment in Real Time

What It Means and Examples of “Miscellaneous” – Beyond the Basics