Unlocking Ethane: The Science Behind the C2H6 Lewis Structure

Unlocking Ethane: The Science Behind the C2H6 Lewis Structure

The C₂H₆ Lewis structure serves as a foundational model for understanding one of the most prevalent hydrocarbons in chemistry—ethane. Far more than a simple diagram of carbon and hydrogen atoms, this structure reveals the shared and unique electron behaviors that define molecular stability, reactivity, and application across industries. From fuel formulation to polymer synthesis, ethane’s behavior hinges on the precise arrangement shown in its Lewis structure, making it indispensable to chemists, engineers, and students alike.

The Core of Ethane: Carbon-Hydrogen Connectivity

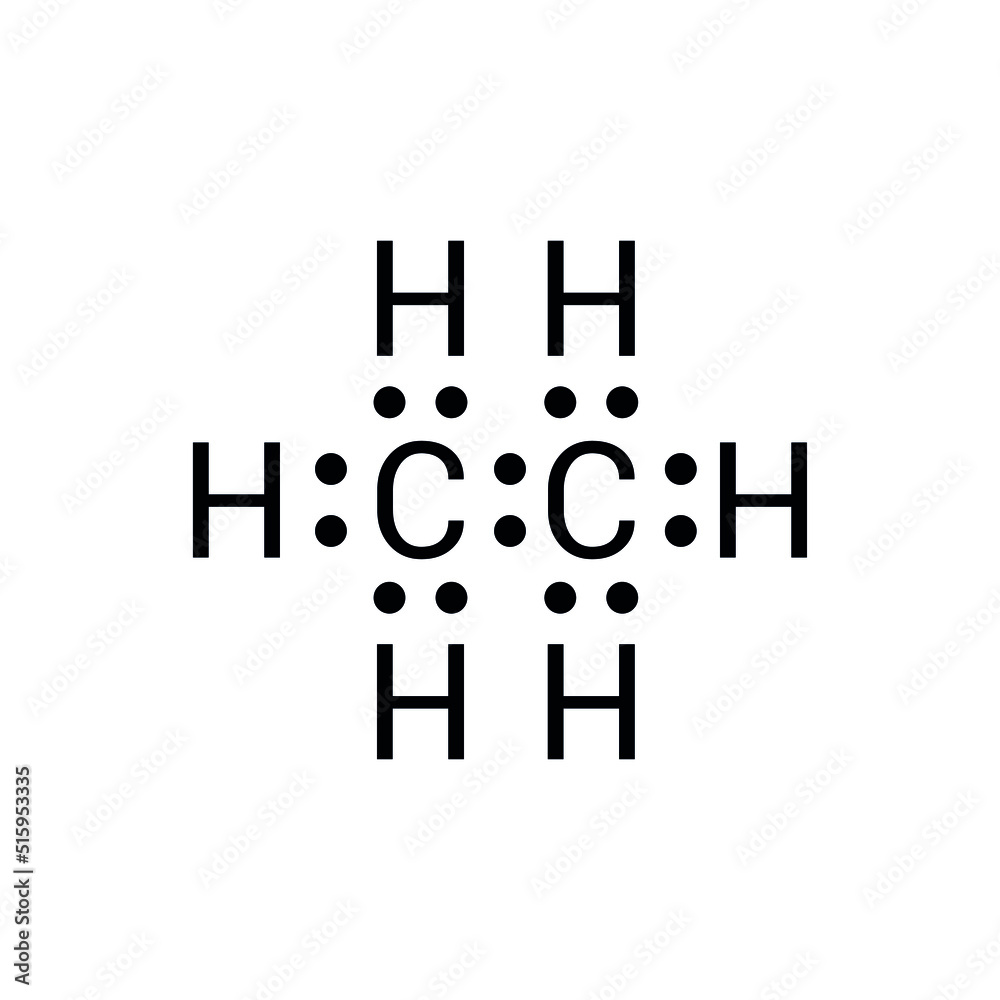

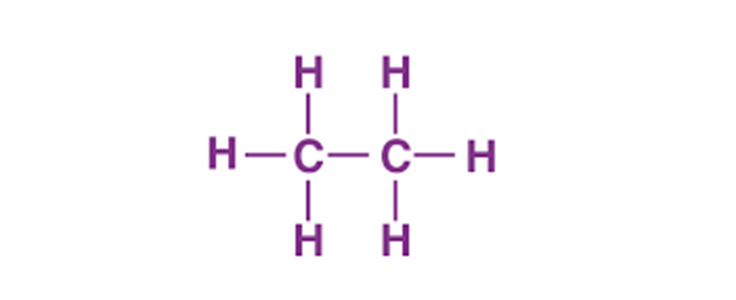

The Lewis structure of C₂H₆ defines the bonding between two carbon atoms and six hydrogen atoms through a system of sigma (σ) bonds and electron distribution that follows Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) principles.

Each carbon atom shares one pair of electrons with the other carbon, forming a single C–C σ bond—this shared pair anchors the molecule’s backbone. Each carbon also forms three C–H sigma bonds, resulting in four valence electrons used entirely in bonding, leaving no lone pairs on the central atoms.

The structure mathematically reflects the exchange of electron pairs: two carbon atoms share one covalent bond, while each forms three bonds with hydrogen atoms, maximizing orbital overlap and minimizing electron repulsion.

This optimal geometry ensures the molecule remains stable and less reactive under standard conditions, a trait critical to its widespread use as a feedstock in petrochemical processes.

Electron Distribution: Delocalization and Bond Character

Though often depicted as alternating single and triple bonds in simplified drawings, the true electron distribution in ethane’s Lewis structure is based on sigma bonding, with no actual electron delocalization. Each C–H bond in C₂H₆ is a stereochemically equivalent sp³ hybrid bond, with bond angles close to 109.5°—a characteristic of tetrahedral geometry. The absence of lone pairs allows efficient orbital non-bonding interactions, contributing to the molecule’s symmetry and chemical inertness.

Each C–H bond exhibits partial covalent character with an effective bond energy averaging around 413 kJ/mol, though again, real bond energy values are derived from spectroscopic and quantum mechanical measurements. The neutral, electron-symmetric nature of the structure minimizes internal strain, enabling ethane’s role as a stable precursor in chemical synthesis.

Resonance and Stability: Why Ethane Resists Reactivity

Unlike unsaturated hydrocarbons such as ethene or acetylene, ethane lacks π-bonds or conjugation, eliminating resonance stabilization. This absence of resonance reduces electron delocalization, making ethane less reactive than its unsaturated counterparts.

According to Lewis theory, the fully localized electron pairs in its σ-framework contribute to the molecule’s low undular polarity and minimal interaction with electrophiles.

Still, ethane is not inert. Under high heat and catalytic conditions, the C–H σ bond can break, initiating free-radical substitution reactions—key to industrial ethylene production.

The Lewis structure thus serves not only as a static snapshot but as a dynamic reference for predicting reaction pathways, showing how bond strength and electron arrangement govern practical transformations.

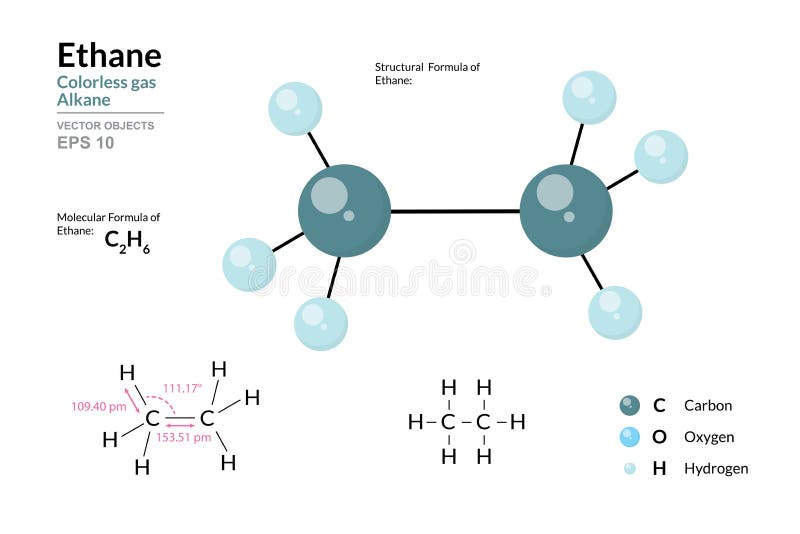

Geometric Precision and Molecular Orientation

The planar arrangement of substituents around each carbon in ethane reflects strict adherence to VSEPR theory. With no lone pairs or additional bonding partners beyond three hydrogens, each carbon adopts a tetrahedral orientation, resulting in a flat molecular framework. This symmetry simplifies spatial analysis and enables accurate predictions of intermolecular forces such as London dispersion, critical in understanding phase behavior and volatility.

In bulk liquid ethane, for instance, these intermolecular interactions determine boiling point (–138.3°C at 1 atm) and density, while in gas form, kinetic energy overcomes weak dispersion forces. The Lewis structure thus provides the geometric baseline from which physical properties emerge, illustrating how electronic configuration directly translates to observable chemistry.

Applications Fueling Industry: From Refining to Materials Science

The real-world significance of the C₂H₆ Lewis structure manifests across multiple sectors. As a primary component of natural gas and petroleum refinery streams, ethane is a vital crackstock—its saturated hydrocarbon nature making it ideal for steam cracking to produce ethylene, the building block of polymers, plastics, and synthetic rubber.

Beyond fuel, ethane’s role extends into laboratory synthesis, where its predictability aids in designing organic transformations. In fuel cells and energy systems, understanding ethane’s stability informs storage and handling protocols, minimizing risks in transport and grid integration. The Lewis structure, though deceptively simple, underpins vast technological infrastructure and innovation.

Modern Insights: Computational Validation and Beyond

Advances in computational chemistry have refined the classical representation of C₂H₆ through quantum mechanical modeling.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations confirm the dominance of σ bonding, while vibrational frequency analyses align closely with Lewis structure predictions.

Related Post

6 Proven Strategies to Outsmart the “This Site Is Not Legal” Trap

From Shakespearean Stages to Modern Screens: The Rise and Evolution of Charlie McDermott

Sonic The Hedgehog Vore: Unpacking a Transformative and Subversive Fandom

June 17 Star Sign: Unlocking Your Cosmic Personality Through One of the Most Dynamic Astrological Signs