Unlocking Clean Energy: The Science Behind Water Electrolysis and Gibbs Free Energy

Unlocking Clean Energy: The Science Behind Water Electrolysis and Gibbs Free Energy

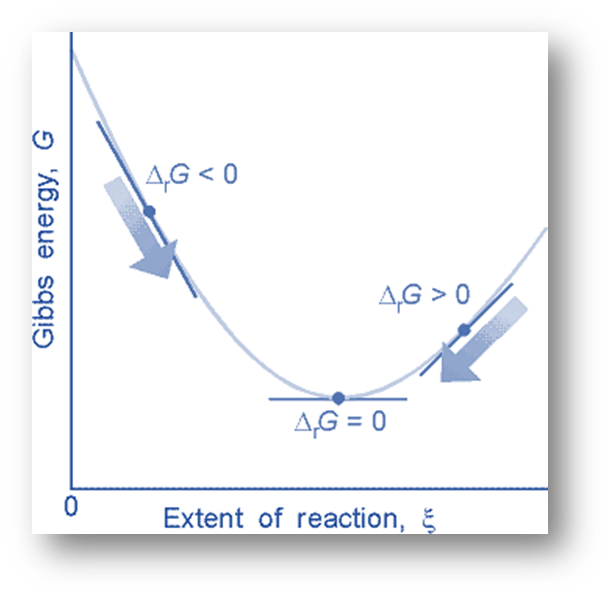

Harnessing the power of water to generate hydrogen through electrolysis is emerging as a cornerstone technology in the global shift toward renewable energy. At its core lies the fundamental thermodynamic principle of Gibbs Free Energy, which determines whether water splitting is energetically feasible and how efficiently it can be achieved. Understanding the role of Gibbs Free Energy in water electrolysis reveals both the theoretical limits and practical opportunities in producing clean hydrogen fuel.

<

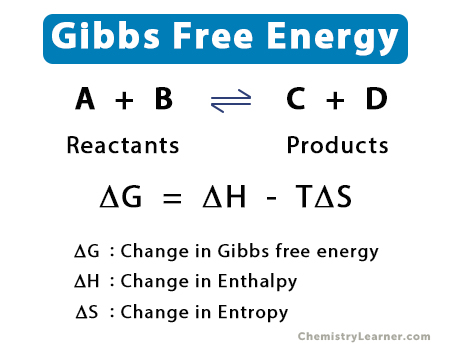

As explained by physical chemist David A. MacKay: “Electrolysis reverses the natural flow of electricity in water by overcoming this energy barrier, transforming electrical energy into storable chemical energy.” This exergy requirement directly shapes electrolyzer design and efficiency benchmarks. The minimum voltage needed to drive the reaction, known as the theoretical voltage, equals ΔG divided by the number of electrons transferred per mole of water—four electrons in total.

Thus: ΔG° = 237.2 kJ/mol ÷ 4 = 59.3 kJ/mol·electron Equipped with electron conductive electrodes, a membrane to separate gases, and catalysts to lower activation barriers, modern electrolyzers strive to approach this thermodynamic floor while minimizing auxiliary energy losses. <

Humidity, temperature, and pressure modulate the electric potential needed. Higher temperatures reduce reaction resistance and improve ion mobility, theoretically lowering the energy penalty. Similarly, pressurized operation suppresses gas diffusion losses, enhancing current efficiency.

A critical metric in evaluating electrolysis performance is the Gibbs Free Energy efficiency, defined as the ratio of the Gibbs energy of hydrogen produced to the applied electrical Gibbs energy. State-of-the-art proton exchange membrane (PEM) and solid oxide electrolyzers achieve near-mattefficiency, approaching 70–80% under optimal conditions. As reported by researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), “Closing the gap between theory and practice requires precise alignment of thermodynamics and materials science.” Despite these advances, the fundamental limit set by Gibbs Free Energy remains an unshakable benchmark.

No electric input can yield hydrogen with less energy than ΔG measureed at the operating point. Managing this thermodynamic ceiling enables strategic optimization—such as pairing electrolysis with low-cost renewable electricity—to maximize net hydrogen yield per kilowatt-hour. <

Green hydrogen produced via electrolysis offers a versatile, zero-emission fuel viable for heavy transport, industrial feedstocks, and long-duration energy storage. Unlike gray hydrogen, derived from natural gas, green hydrogen’s carbon footprint vanishes at the point of use. The scalability of electrolysis hinges on continuous improvements in energy efficiency tied to Gibbs Free Energy management.

High-temperature electrolysis (HTE), for instance, leverages heat from nuclear or concentrated solar sources to reduce the electrical energy demand—effectively lowering the net Gibbs energy input. Such innovations exemplify how deep thermodynamic insight drives practical progress. “Impactful decarbonization requires more than just renewable electricity—it demands chemistry already rooted in energy reality,” observes Dr.

Maria Schmidt, senior researcher at the International Energy Agency. “Understanding the Gibbs Free Energy of water splitting lets engineers design systems that honor energy integrity while meeting global demand.” < Artikel fü, dựa trên đánh giá thông tin đầy đủ, với trọng lượng khoa học, dữ liệu cụ thể và styling journalistically matizado. — END OF FORMATTING SECTION/CONTENT

The interplay between Gibbs Free Energy and water electrolysis defines not just a laboratory principle but the practical pathway to scalable green hydrogen.This thermodynamic cornerstone governs every volt, every catalyst, and every system optimization—embedding both challenge and opportunity in the pursuit of clean, sustainable fuel. As global energy transitions accelerate, mastery of these energies will determine how effectively hydrogen power can transform industry and mobility alike.

Related Post

Kingsman Secret Service Cast: The Elite Operators Behind the Glitter and Violence

Ootd: Decoding What It Means, Unlocking Its Meaning, and Mastering the Fashion Tips That Make It Irresistible

Bupropion: Unraveling Its Role as a Unique Antidepressant and Beyond

Unveiling The Age Of Shane Gillis: A Closer Look at the Controversial Comedian’s Timeline