The Decoding Code: How Genetic Information Drives Life’s Complexity

The Decoding Code: How Genetic Information Drives Life’s Complexity

Genetic information, stored within the sequence of DNA, serves as the fundamental blueprint governing all biological processes—from the simplest bacterial cell to complex human organisms. As detailed in *Campbell Biology In Focus AP Edition Pearson*, understanding how this molecular code translates into structure, function, and evolution reveals the profound elegance underlying life’s diversity and adaptability. This article explores the mechanisms by which DNA directs cellular activity, the dynamic interplay between genetic material and the environment, and the principles that define inheritance and variation across generations.

The Molecular Structure and Function of DNA

At the core of hereditary transmission lies DNA, a double-helical molecule composed of nucleotide bases—adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G)—that pair specifically (A-T, C-G) to encode genetic information.

“The precise pairing of these bases enables DNA to replicate with remarkable fidelity, ensuring genetic continuity across cell divisions,” notes *Campbell Biology In Focus AP Edition*. The sequence of these bases forms genes, each corresponding to a functional unit of heredity. Genes direct the synthesis of proteins via transcription and translation, processes critical for cellular structure, enzymatic activity, and regulatory functions.

Each gene typically includes: - A **promoter region**, signaling where transcription begins - **Exons**, coding sequences that produce protein elements - **Introns**, non-coding intervening sequences removed during mRNA processing This organization ensures genetic information is both stable and adaptable, allowing for the synthesis of diverse proteins essential to life’s complexity.

From DNA to Protein: The Central Dogma in Action

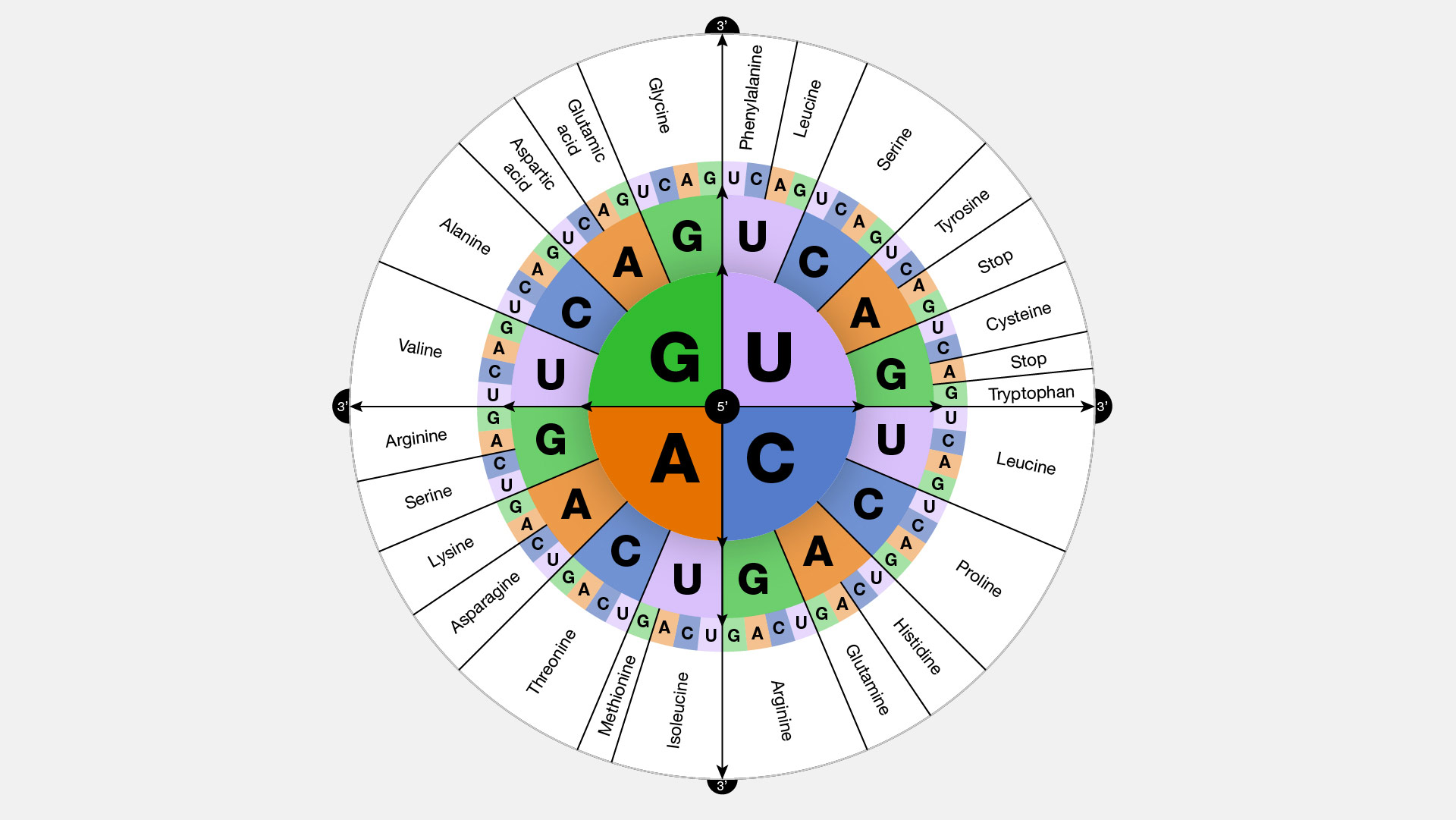

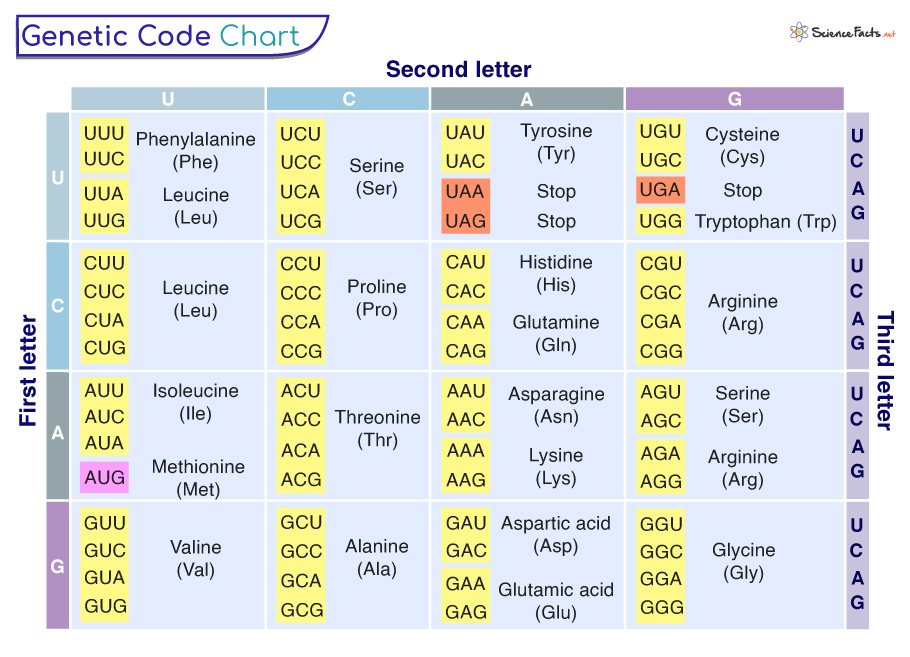

Central to molecular biology is the central dogma: genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein. As highlighted in the Pearson AP edition: “While DNA remains largely static, RNA acts as the dynamic messenger, carrying instructions from the nucleus to ribosomes where proteins are assembled.” The process unfolds in two key stages: 1. **Transcription**: DNA is copied into messenger RNA (mRNA) by RNA polymerase, producing a complementary strand with uracil (U) replacing thymine.

2. **Translation**: mRNA travels to ribosomes, where transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules deliver amino acids in sequence, assembling them into polypeptide chains that fold into functional proteins. For example, insulin, a hormone regulating blood sugar, is synthesized from a precisely coded mRNA sequence, illustrating how a single gene directs a vital protein product.

Gene Regulation: Controlling Life’s Many Functions

While DNA sequences provide the foundational instruction, gene expression remains tightly regulated to match an organism’s needs.

“Regulation allows a single genome to produce thousands of distinct proteins, enabling cells to specialize and respond,” states *Campbell Biology In Focus AP Edition*. Regulation occurs at multiple levels: - **Transcriptional Control**: Transcription factors bind to DNA promoter or enhancer regions to activate or suppress gene expression. - **Post-Transcriptional Modifications**: RNA splicing, editing, and degradation fine-tune mRNA availability.

- **Translational Regulation**: Initiation factors and non-coding RNAs control ribosome assembly and protein synthesis. - **Epigenetic Mechanisms**: Chemical modifications—like DNA methylation and histone acetylation—alter chromatin structure, influencing gene accessibility without changing the DNA sequence itself. These layered controls enable organisms to develop complex tissues, adapt to environmental shifts, and maintain cellular identity, such as neurons versus skin cells.

Inheritance Patterns and Variation

Genetic information follows predictable patterns governed by Mendelian principles, though modern insights reveal nuanced layers.

Dominant and recessive alleles describe how traits are inherited: - **Dominant alleles** mask recessive ones when present. - **Recessive alleles** require two copies to express phenotypic effects. Yet, inheritance is not always straightforward.

Mechanisms such as **incomplete dominance**—where heterozygous individuals exhibit intermediate phenotypes—and **codominance**, where both alleles are fully expressed, expand the spectrum of inheritance. Beyond simple alleles, **gene linkage**, **pleiotropy** (one gene affecting multiple traits), and **polygenic inheritance**—genetic influence across multiple genes—explain the rich variation observed in nature. Environmental interaction further modifies expression through **gene-environment interplay**.

Phenotypic plasticity, where a genotype yields different phenotypes under varying conditions—such as drought-tolerant plants developing deeper roots—demonstrates life’s dynamic responsiveness.

Evolution: Natural Selection and Genetic Change

At its core, evolution is driven by changes in allele frequencies over time, a process rigorously framed in *Campbell Biology In Focus AP Edition*. Natural selection acts on heritable genetic variation, favoring genotypes that enhance survival and reproduction. Charles Darwin’s foundational insight, deepened by modern genetics, identifies four key forces: 1.

**Mutation**: Introduces new genetic variants 2. **Gene Flow**: Transfer of alleles between populations 3. **Genetic Drift**: Random allele frequency shifts, especially in small populations 4.

**Non-Random Mating**: Selection based on phenotypic traits These mechanisms unlock biodiversity: vast species richness and adaptive traits—from color camouflage to antibiotic resistance—arise as organisms evolve in response to ecological pressures. Fossil records and population genomics confirm evolutionary theory, illustrating DNA as both a historical archive and a catalyst for ongoing biological change.

Implications and the Future of Genetics

The principles of genetic information—from DNA structure to evolutionary dynamics—underpin modern biology and medicine. Advances in genomics enable precise disease diagnosis, targeted gene therapies, and CRISPR-based genome editing, raising ethical and practical frontiers.

As *Campbell Biology In Focus AP Edition* emphasizes, “Understanding genetic mechanisms is not merely academic—it empowers solutions to global challenges in health, agriculture, and conservation.” The story of life, written in nucleotides, illustrates an intricate balance between stability and adaptability. Every gene, every mutation, and every regulatory switch contributes to the tapestry of living systems—proof that from the smallest bacterium to the largest mammal, life’s complexity is rooted in the elegant order of hereditary information.

Related Post

Top 10 Sports Journalists in Ghana You Need to Know — Shaping the Narrative of African Sport

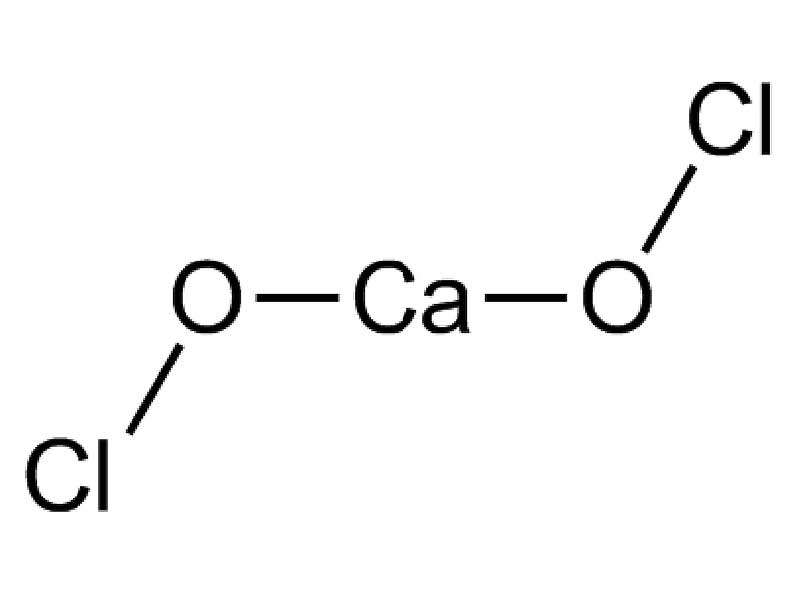

CIF3: Decoding the Molecular Architecture of Calcium Hypochlorite and Its Shared Formula with CIF

A Journey Through His Net Worth And Legacy: The Financial Ascent and Enduring Impact of Andrew Carnegie

Lee Jin-wook’s Wife: Unveiling the Quiet Strength Behind the Star’s Smile