Stratified Squamous Non-Keratinized: The Versatile Lining of the Oral and Upper Respiratory tracts

Stratified Squamous Non-Keratinized: The Versatile Lining of the Oral and Upper Respiratory tracts

Nestled within the complex architecture of the human body lies a critical yet often overlooked tissue: stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium. This resilient cellular layer lines the mucosal surfaces of the oral cavity, esophagus, and parts of the upper respiratory tract, where it performs essential protective and functional roles. Unlike its keratinized counterparts found in skin, this non-keratinized variant maintains moisture and flexibility, enabling it to withstand the dynamic environment of swallowing, speech, and airflow.

Its unique structure ensures durability without the rigidity that would otherwise hinder normal physiological processes.

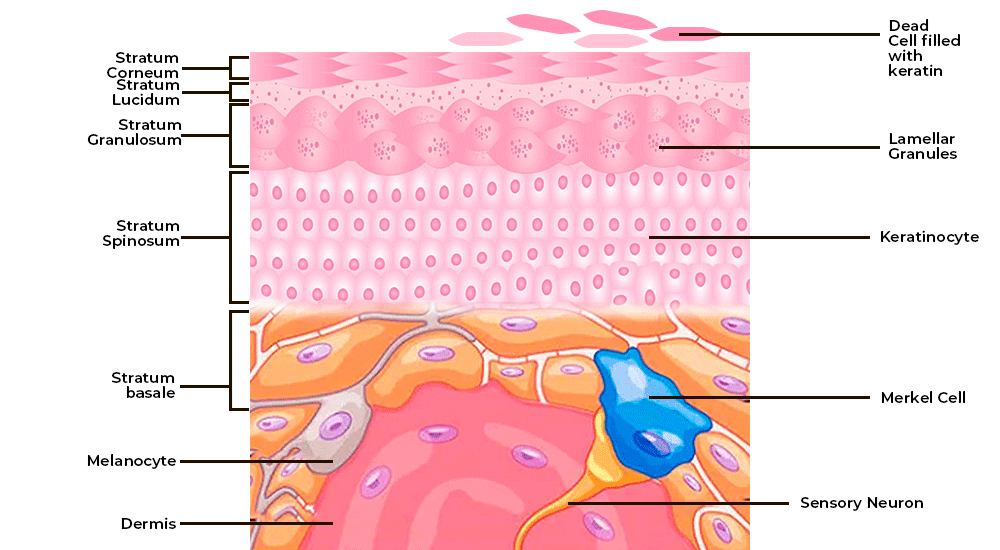

To understand the significance of stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium, one must first consider its microscopic architecture. This tissue consists of multiple layers of squamous cells—flat, polyhedral cells tightly joined at desmosomes—to form a barrier capable of resisting mechanical stress and exposure to pathogens.

Beneath this surface, basal cells continuously divide, replenishing the lining to maintain integrity even after routine abrasion during eating or drinking. “This dynamic balance of cell renewal and structural cohesion allows the epithelium to handle constant friction without losing its protective function,” explains Dr. Elena Marlowe, a mucosal biologist at the Institute of Translational Medicine.

“It’s nature’s engineering—self-repairing, adaptive, and highly efficient.”

At the cellular level, stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium features specialized kerat cytoskeletal components distributed unevenly across its layers. In this non-keratinized subtype, a complete separation from the keratin filaments permits ongoing hydration and flexibility, critical for tissues subjected to frequent moisture shifts. The basal layer houses stem cells fed by growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which regulate proliferation and differentiation.

As cells migrate upward through the five to ten-cell-thick epithelium, they thicken, flatten, and lose nuclei and cytoplasmic organelles—a process known as cornification reversal—resulting in a barrier impermeable to microbes yet porous enough to allow selective nutrient absorption and sensory feedback.

This tissue’s functional versatility extends beyond simple coverage. In the oral cavity, it safeguards underlying connective tissues from mechanical trauma caused by food bolus transit and dental abrasion.

It also serves as the first line of defense against pathogens: the saliva continuously washes away microbes, while antimicrobial peptides secreted by underlying immune cells patrol the epithelial surface. In the esophagus, despite harsh acid exposure from reflux, this epithelium remains resilient—provided it remains uncompromised. “When this layer is breached—by acid, infection, or inflammation—conditions like oral candidiasis or esophageal dysplasia can develop,” notes Dr.

Marlowe. “Maintaining its integrity is fundamental to preventing systematic disease.”

Clinical relevance of stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium is underscored in dermatology and oncologic medicine. Biopsies of oral or esophageal lesions often begin with histopathology to determine whether the epithelium is stratified squamous non-keratinized and to detect early dysplastic changes.

Cancers arising in these tissues—squamous cell carcinomas—originate from epithelial cells within this layer, emphasizing the clinical importance of monitoring its health. Regular screening for high-risk populations, combined with avoidance of provoked irritants such as tobacco and excessive alcohol, is critical. “Early detection hinges on understanding the normal behavior and vulnerabilities of this epithelial type,” says Dr.

Rajiv Nair, a clinical pathologist specializing in head and neck oncology.

Beyond clinical contexts, this tissue exemplifies biological adaptation. Its non-keratinized state reflects an evolutionary compromise: permanent keratinization would impair moisture retention and elasticity, essential for humid environments.

Instead, the stratified squamous non-keratinized lining optimizes protection without sacrificing function. Lifestyle factors such as diet, smoking cessation, and oral hygiene directly influence its resilience, proving that preventive care at a microscale yields lasting health benefits.

In essence, stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium represents a marvel of physiological engineering—mobile, hydrated, and resilient.

It sustains the vital functions of vital body passages while adapting to constant environmental challenges. Recognizing its role deepens our appreciation for the subtle yet profound mechanisms maintaining human health every day. Maintaining its health is not reserved for crisis—it begins with consistent, informed care rooted in scientific understanding.

Related Post

Lady Sonia: The Life and Career of a Controversial Figure Who Redefined Royal Expectations

Zverev Tennis Racket: The Counterforce Redefining Elite Play

VW Golf 7 Variant Facelift 2017: Sharp Design, Proven Reliability, and Driveability That Still Drives Demand

Unlocking the Potential of Renewable Energy: The Academic Imperative Driving Global Transformation