Molecular Shape and Electron Geometry: The Invisible Blueprint Shaping Chemistry’s Behavior

Molecular Shape and Electron Geometry: The Invisible Blueprint Shaping Chemistry’s Behavior

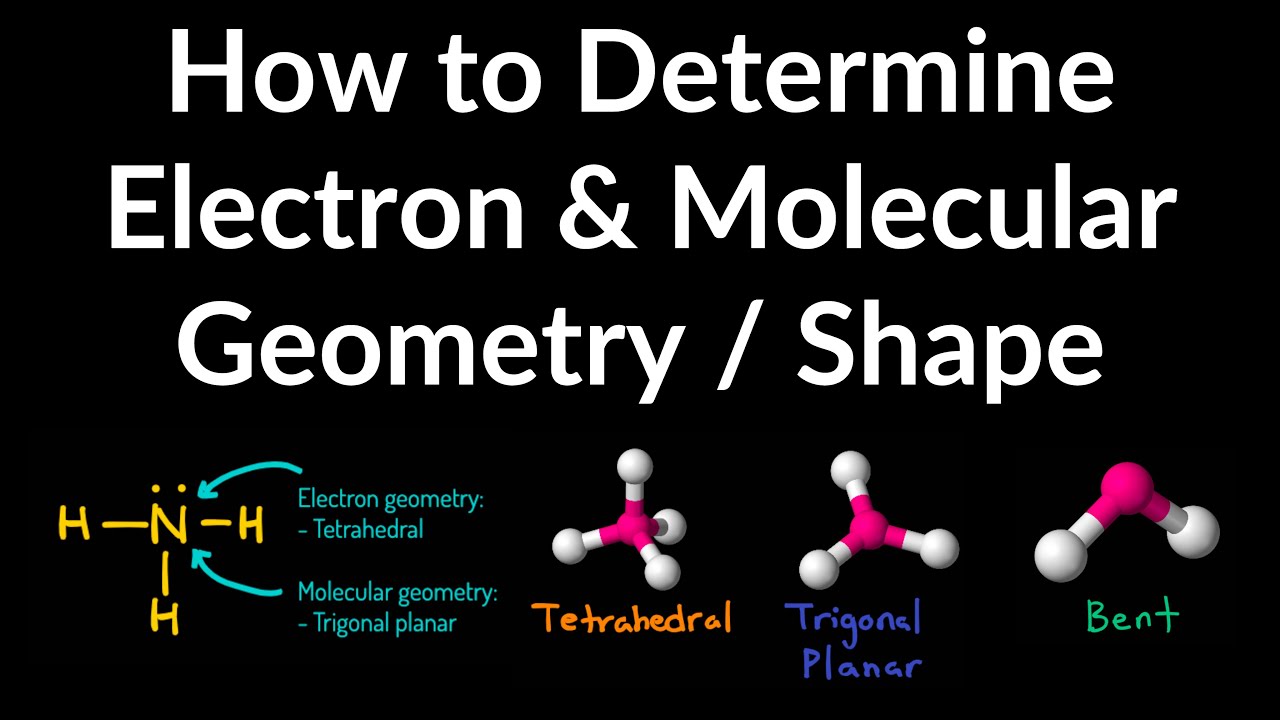

At the heart of molecular science lies a silent, invisible blueprint—molecular shape and electron geometry—dictating how atoms bond, react, and interact. Far from arbitrary, the three-dimensional arrangement of electrons around a central atom determines everything from a compound’s stability to its function in biological and industrial processes. This fundamental concept, rooted in Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory, reveals why water is bent, methane is tetrahedral, and ammonia appears pyramidal—each form a direct consequence of electron distribution.

The Core Principles: Electron Pairs and Spatial Organization

Molecular geometry begins with electrons. Atoms surround their nuclei with valence electrons capable of forming bonds and lone pairs. According to VSEPR theory, these electron pairs repel one another, compressing into spatial configurations that minimize repulsion—this defines electron geometry, while molecular geometry accounts only for bonded atoms.The distinction is crucial: a central atom with four bonding pairs adopts a tetrahedral electron geometry, but only three bonded atoms result in a molecular shape resembling a pyramid with a watery bend. “Every molecule tells a story written in electron repulsion,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a physical chemist at MIT.

“The spatial ordering is not random—it’s the result of a careful dance of forces that shapes reactivity, polarity, and interactions at the nanoscale.” The number of electron pairs—whether bonding or lone—determines symmetry. Two pairs yield linear geometry, three linear or trigonal planar, four tetrahedral, five trigonal bipyramidal, and six octahedral. Each configuration arises from geometric efficiency in maximizing distance between electron clouds.

From Theory to Tangible: Real-World Molecular Architectures

Understanding electron geometry allows scientists to predict molecular behavior with precision. Take carbon dioxide: with two double bonds around a central carbon, it assumes a linear shape due to two electron regions. No lone pairs compress angles to 180 degrees, yielding a straight configuration that impacts infrared absorption and environmental persistence.In contrast, ammonia (NH₃) features three bonding pairs and one lone pair. The lone pair exerts greater repulsion, compressing the H–N–H bond angle to approximately 107 degrees—less than the ideal tetrahedral 109.5°. This bent shape makes ammonia highly polar and capable of hydrogen bonding, critical in biochemical reactions and detergents.

Water, a quintessential example, exhibits a bent geometry driven by two bonding pairs and two lone electrons on oxygen. The lone pair repulsion forces O–H angles close to 104.5°, creating a polar molecule essential for life. Without this precise geometry, water’s unique properties—solvent power, high heat capacity—would not exist.

< poets-style>“The shape of a molecule isn’t just a geometric curiosity—it’s the foundation of its chemical identity,” remarks Prof. Rajiv Nair, molecular modeler at Stanford University. “From catalysts in chemical factories to signaling molecules in cells, geometry dictates function.” Electron geometry also explains anomalies in molecular behavior.

Consider sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆): six bonding pairs around sulfur assume an octahedral configuration, minimizing repulsion in a structure so symmetrical it’s used in laser systems. Conversely, molecules like clathrate hydrates adopt cage-like geometries as water molecules trap guest molecules—geometry enabling storage of gases at ambient conditions.

These insights recalibrate predictions of bond angles and molecular stability, reinforcing geometry’s indispensable role. In pharmaceuticals, molecular shape guides drug design. Active pharmaceutical ingredients must fit precisely into biological targets—shape-mismatched drugs fail.

Structure-based drug discovery uses electron geometry as a blueprint, ensuring synthetic molecules align spatially with enzyme pockets or receptor sites.

Materials science exploits geometric principles to develop 2D materials, superconductors, and metamaterials with tailored optical and electronic properties—all rooted in the atomic-scale dance of electrons. Quantum mechanics deepens this understanding, revealing that electron geometry emerges from probabilistic electron clouds rather than fixed points. Yet, the VSEPR model remains a practical and powerful tool—bridging theory and laboratory insight.

In essence, molecular shape and electron geometry form the invisible scaffolding of chemistry. They govern reactivity, stability, polarity, and function across scales—from biological macromolecules to nanoscale devices. Mastery of this concept empowers scientists to predict, manipulate, and design matter with intent—a quiet revolution in materials, medicine, and technology.

Understanding electron geometry is not merely academic; it is the key to unlocking innovation in an increasingly molecularly engineered world. As research evolves, so too does the clarity and power of this foundational concept—ständige science in motion, one bond at a time.

Related Post

Where Excellence Meets Opportunity: Top Nursing Schools Shaping America’s Future Caregivers

Brazil 1985: The Year Democracy Awakened After Decades of Military Rule

Wordle.Clue: Decoding the Words Behind Today’s Most Challenging Clues

Honoring Memories: Exclusive Tributes from Jp Holley Funeral Home at Columbia Sc