Mastering Perfect Rice: The Essential Guide to Rice to Water Ratio in Electric Rice Cookers

Mastering Perfect Rice: The Essential Guide to Rice to Water Ratio in Electric Rice Cookers

For millions relying on rice as a dietary staple, achieving consistently fluffy, perfectly cooked grains remains an enduring culinary challenge—especially when using automatic rice cookers. The secret lies not in programmable buttons alone, but in mastering the precise rice-to-water ratio, a foundational variable that determines texture, aroma, and mouthfeel. Unlike oven-baked or stovopot methods, electric rice cookers demand accuracy in this ratio to ensure optimal absorption and steaming, transforming raw grains into tender, separate grains every time.

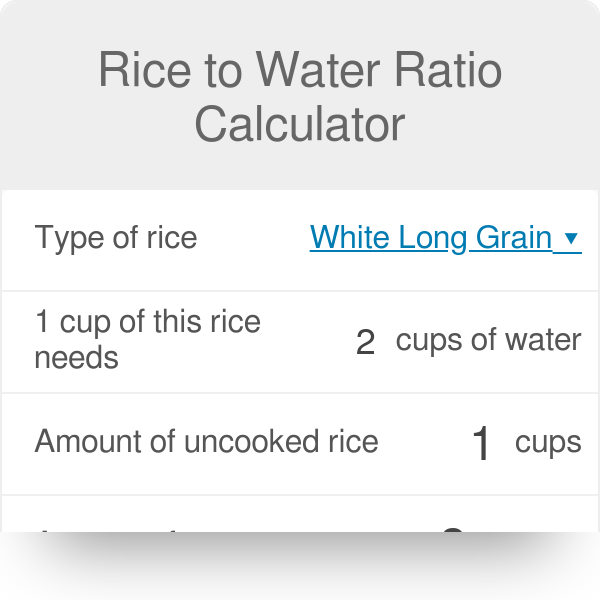

Understanding and adhering to the correct ratio empowers home cooks and professionals alike to consistently replicate restaurant-quality rice at home. The rice-to-water ratio is far from arbitrary. While different rice types—white, brown, basmati, jasmine—react uniquely to moisture and heat, a scientifically grounded baseline guides optimal cooking.

For white short-grain rice, the universally recommended ratio is **1 part rice to 1.2 to 1.3 parts water**. This slightly higher water volume accounts for the grain’s high starch content, which swollen during cooking releases moisture essential for fluffiness. Using too little water results in hard, crunchy grains; too much can lead to a mushy texture or even unabsorbed, pasty results.

Take Japanese short-grain rice, the ideal choice for sushi, tonkatsu rice, or everyday meals. With 1:1.3 water, it achieves that signature creamy inside and slightly firm exterior. In contrast, basmati rice, prized for its long grains and aroma, requires a lower ratio—typically **1:1.1 to 1:1.2** water—because its lower starch content and wider grain shape absorb less liquid without becoming sticky.

The key factor is not just volume, but consistency: coarse versus fine grain, polished or unpolished, and even altitude or ambient humidity can subtly influence results. Cooks often adjust ratios in practice, guided by texture outcomes rather than rigid rules.

A frequently overlooked nuance involves grain prep: rinsing white rice thoroughly before cooking removes excess surface starch, preventing gummy clumps and ensuring even hydration.

For brown rice and black rice, which contain bran layers that swell more during cooking, increasing water to **1:1.4 or higher** enhances tenderness and digestibility. Some experts recommend pre-soaking these varieties for 30 minutes to begin hydration, reducing overall cooking time and improving moisture retention. This step, combined with precise ratio calibration, elevates performance with stubborn or high-fiber rices.

Rice cookers automate much of the process, but their effectiveness hinges entirely on user input—most critically, the water-to-rice proportion. Many modern models feature digital displays and preset programs, yet without the correct ratio, even the most advanced cooker delivers subpar results. “A wheel provides timing and heat, but the water ratio provides texture,” notes Dr.

Elena Marquez, a food science researcher at the Institute of Functional Grains. “It’s the molecular bridge between raw grain and ideal bite.”

Practical application reinforces the importance of precision. For standard white rice, a ratio of 1:1.2 water delivers soft, separate grains ideal for stir-fries, sushi, or side dishes.

Brown rice typically benefits from 1:1.3 water, promoting even steaming and extended cooking that unlocks nutty flavors. For longer-grained varieties like jasmine or Calrose, the 1:1.1 range prevents excessive stickiness while maintaining aroma and lightness. Home cooks testing variations often find that a 5–10% adjustment—such as using 1:1.15 for medium-grain rice—makes measurable differences in texture.

Environmental variables like altitude also influence outcomes. At higher elevations, where boiling water evaporates faster, slight increases in water volume (up to 10–15%) may be necessary to maintain steaming efficiency. Similarly, variations in rice moisture content due to packaging or storage can shift optimal ratios by a fraction—underscoring the value of calibrated, repeatable measurements.

Measurement tools also matter. Bulk rice often varies by size and density; using a kitchen scale ensures consistency beyond volume measurements. A simple conversion—1 cup uncooked rice equals roughly 180–190 grams—provides a quick benchmark, though professional kitchens may weigh individual samples.

Even utensils differ: if using a measuring cup, leveling with a straight edge ensures 1 cup of dry rice weighs precisely 180 grams, a critical step for reproducibility.

Optimizing Ratios for Different Rice Types: A Comparative Guide

- **White Short-Grain Rice** – Ideal for sushi and everyday meals. Water-to-rice ratio: 1:1.2 to 1:1.3 Result: Fluffy, separate grains with creamy interior.Pre-cooking step: Rinse thoroughly, then soak 30 minutes for best texture. - **Brown Rice** – Nutrient-rich whole grain with bran layer. Water-to-rice ratio: 1:1.3 to 1:1.4 Result: Tender with nutty flavor after extended, even steaming.

- **Basmati Rice** – Fragrant long-grain, low-starch content. Water-to-rice ratio: 1:1.1 to 1:1.2 Result: Light, separate grains with pronounced aroma. - **Jasmine Rice** – Aromatic Thai staple.

Water-to-rice ratio: 1:1.2 to 1:1.3 Result: Slight stickiness enhances binding in curries and fried rice. - **Black Rice (Heirloom)** – Deep purple grain with high anthocyanins. Water-to-rice ratio: 1:1.3 to 1:1.4 Result: Tender texture with rich, earthy flavor after hydration.

The chemistry behind these ratios stems from starch gelatinization: during cooking, rice absorb water, swelling starches until they burst, creating moisture pockets that define a grain’s mouthfeel. Too little water prevents full gelatinization; too much dilutes structure, leading to softness or slurry. The ideal balance ensures grains cook through without over-absorbing, delivering the transformation from hard, opaque kernels to soft, millable perfection.

User experience consistently reflects this principle. Home cooks frequently cite texture as the primary differentiator. “My house always made gummy rice until I mastered the 1:1.25 ratio,” shares Maria Chen, a home cook in Portland, Oregon.

“Now my jasmine rice fluffs up light, leaving no hard bits—proof that small changes matter.” Professional chefs echo this precision. Chef Hiroshi Tanaka of Tokyo’s Rice & Fire Kitchen insists, “The cooker is just a tool. The secret is the water: it’s where the science meets the soul of rice.”

Environmental adaptation remains key.

Cooks in humid climates sometimes increase water by 5% to compensate for faster evaporation, while those at high altitudes may expand ratios by up to 15% to maintain steaming efficiency. Even time of harvest affects grain density—older barley rice requires more water to achieve similar fluffiness as fresher crops.

For consistent results, adopt a methodical approach: measure rice precisely, rinse as instructed, adjust water ratio by type and environment, and time cooking with accuracy.

Use scale verification where possible, and maintain grain prep consistency. Documenting adjustments based on texture feedback builds expertise over time, turning experimentation into mastery.

Science and Sensory: What Happens Under the Cooker’s Surface

The rice cooker’s inner chamber replicates a precisely controlled steaming environment.Inside, rice grains absorb water, burst surface starches, and gradually expand. At around 100°C, moist heat gelatinizes the outer layers while preserving core firmness. The automatic switch to “keep warm” prevents overcooking but requires the initial absorption phase to succeed—a process entirely dependent on correct moisture.

“The cooker does the work, but only the right amount of water makes it reliable,” explains Dr. Marquez. Moisture movement follows physical principles: water migrates by capillary action into dry grain, equalizing internal moisture and enabling starch gelatinization.

The 1:1.2 ratio ensures sufficient capillary pressure without overwhelming the grains’ structural integrity. Brown rice benefits from the extended steaming phase in the cooker’s bottom heating element, unlocking enzymatic activity that softens the bran and deepens flavor—processes that demand both time and precisely controlled hydration.

Controlling texture extends beyond the cooker’s settings.

Cooling cooked rice properly, ideally within 30 minutes, allows remaining moisture to redistribute, enhancing firmness and preventing sogginess. Storing it loosely wrapped in paper, rather than airtight containers, maintains ideal moisture balance. These practices, combined with accurate ratio use, complete the cycle from raw grain to served perfection.

In practice, mastering rice-to-water ratio transforms uncertainty into confidence. A single cup of rice—measured, rinsed, and cooked—becomes a variable constrained by physics and chemistry, yielding predictable excellence. Whether cooking for one or a family of six, this precision ensures rice remains not just a side dish, but a highlight centered on texture, aroma, and consistency.

Ultimately, the rice to water ratio is the cornerstone of perfect rice. In electric cookers, it is the most critical variable—simplicity masked by profound influence. By respecting this ratio, cooks unlock rice’s full potential: fluffy, fragrant, and texturally ideal every time.

For rice lovers and culinary aspiring alike, mastering this balance is not just technique—it is art, science, and satisfaction distilled in a single grain.

Related Post

Unknown Predators Unleashed: Tigers in South America’s Hidden Wild Frontiers

Unveiling the Mystery Behind the Instagram Girl Viral MMS Sex Phenomenon

How Orange’s Mobile Private Networks Are Transforming Digital Connectivity

22 July A Powerful Look At Terrorism: Unraveling a Global Threat Decades After the Bombings