<strong>Mastering Genetics: The Dihybrid Cross Explained with Precision and Power</strong>

Mastering Genetics: The Dihybrid Cross Explained with Precision and Power

Understanding inheritance through multiple traits is a cornerstone of classical genetics, and the dihybrid cross remains one of the most powerful tools in this domain. More than a theoretical exercise, the dihybrid cross reveals how two gene pairs interact when passed from parents to offspring. This analysis enables scientists and students alike to predict complex inheritance patterns, uncovering rules governing trait distribution across generations.

By examining the fusion of two independently inherited characteristics—such as seed color and plant height—this cross provides a window into Mendelian genetics at its most dynamic.

The foundation of the dihybrid cross rests on Gregor Mendel’s pioneering work in the 19th century, though its formal modeling emerged decades later with the formalization of genetic linkage and Punnett square applications. The dihybrid cross investigates the simultaneous inheritance of two traits, each controlled by a different gene located on different chromosomes—or, in simpler models, presumed to assort independently.

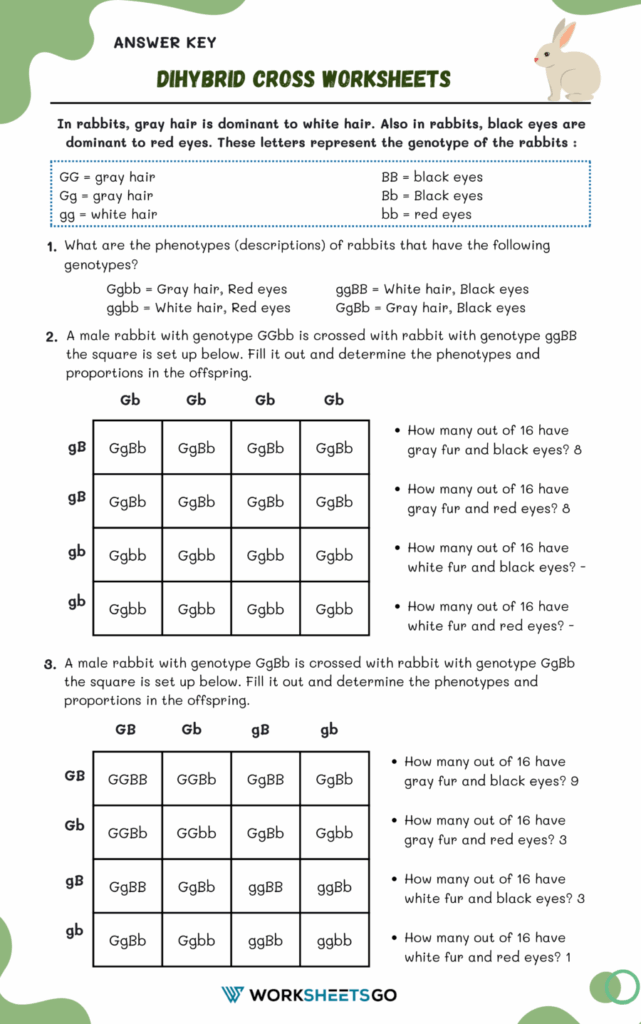

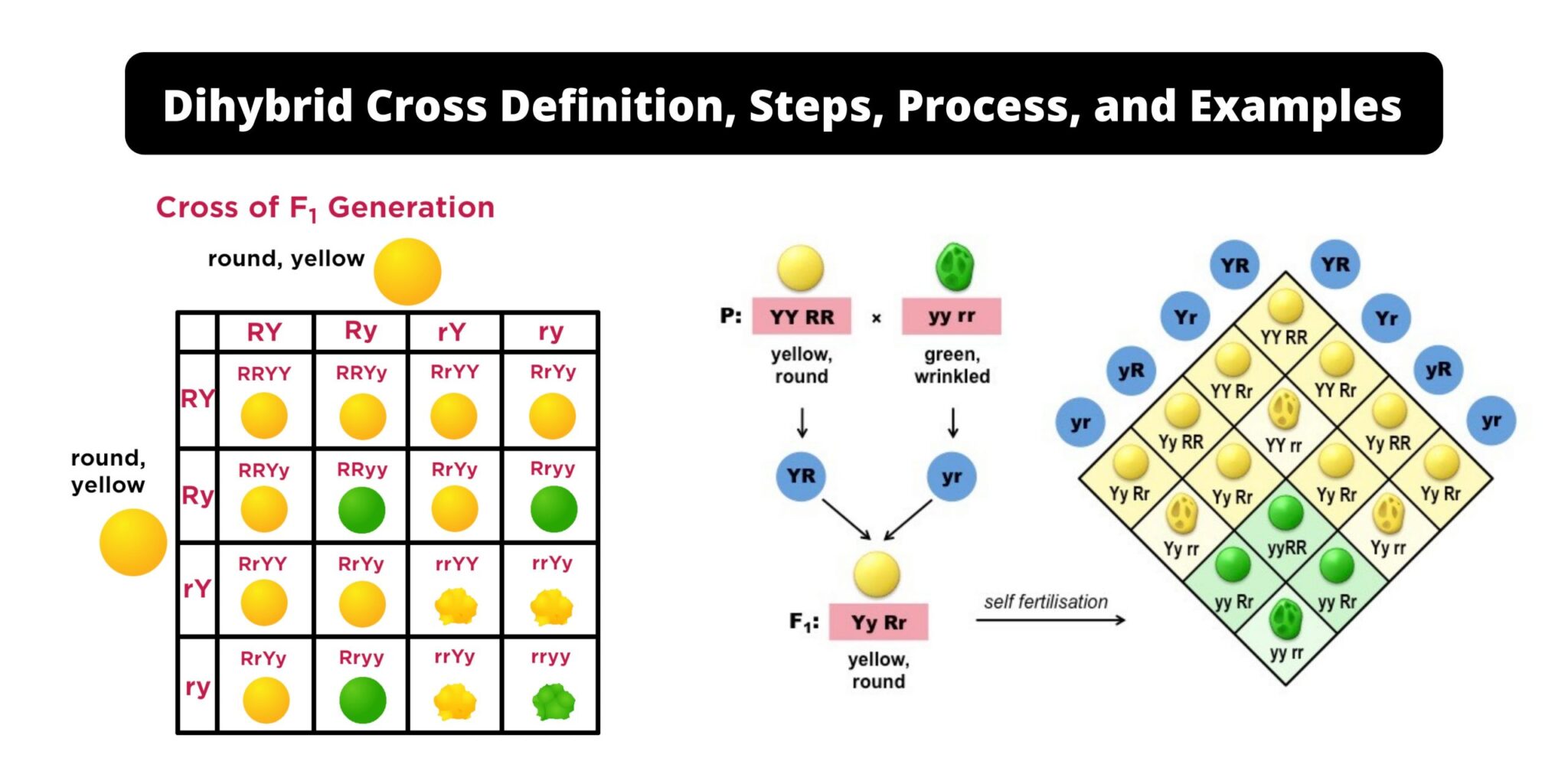

According to classical Mendelian principles, alleles for each gene segregate independently during gamete formation, following what we now recognize as the law of independent assortment. Defining the Genetic Framework Each trait in a dihybrid cross involves two alleles: one dominant and one recessive. For example, consider a plant species where seed color (Y = yellow, y = green) and seed shape (R = round, r = wrinkled) are independently inherited.

Genotypic combinations like YR (yellow, round), Yr (yellow, wrinkled), yyR (green, round), and yyr (green, wrinkled) form the basis for cross calculations. With both parents heterozygous for both traits—YyRr × YyRr—the resulting offspring exhibit a predictable ratio shaped by probabilistic allele combinations.

The dihybrid cross relies on Punnett square methodology expanded across two genes.

Although visualizing a 4×4 grid for two traits may seem daunting, this systematic breakdown ensures clarity: - Each parent produces four distinct gamete types—YR, Yr, yR, yr—drawn from independent allele segregation. - Combining all gametes across 16 (4×4) possible pairings yields a phenotypic ratio of 9:3:3:1 when tripling phenotypic expression—yielding powerful predictive power. This ratio —9 dominant:3 of one heterozygous combination :3 of the other, and 1 homozygous — encapsulates the essence of independent assortment.

As geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan observed, “The dihybrid cross is not merely a mathematical exercise, but a physical testament to how genes shuffle their inheritance.”

Real-World Implications and Applications The dihybrid cross is foundational in fields ranging from plant and animal breeding to medical genetics. In agriculture, breeders leverage this model to predict offspring traits such as drought tolerance combined with pest resistance, accelerating hybrid development. In human genetics, while many disorders involve linked genes that violate independent assortment, understanding dihybrid principles helps interpret patterns in multifactorial inheritance—particularly in conditions influenced by multiple independently contributing loci.

Consider cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia, both autosomal recessive disorders. While their inheritance doesn’t follow a 9:3:3:1 ratio, dihybrid logic aids in carrier probability calculations when multiple recessive traits coexist in a pedigree. Moreover, advances in genomic technologies—CRISPR and genome-wide association studies—rely indirectly on classical dihybrid logic to model polygenic risk and trait co-segregation across populations.

Phenotypic Patterns Unpacked The 9:3:3:1 ratio, while elegant, reflects an idealized scenario. In real-world organisms, linked genes and epistatic interactions often distort expectations. For instance, genes on the same chromosome may assort less independently, reducing dihybrid ratios.

Epistasis—where one gene masks another’s expression—further complicates outcomes. However, the dihybrid cross remains a robust starting point, providing a baseline for detecting deviations that reveal deeper genetic mechanisms.

“The true value of the dihybrid cross lies not only in its simplicity, but in its ability to expose complexity when carefully applied.”

Modern genetics builds on Mendel’s framework.

The dihybrid cross, once a theoretical construct, now integrates with statistical models, computational simulations, and high-throughput sequencing. Yet its core purpose endures: to decode how two gene pairs interact, predict genotypes and phenotypes, and illuminate inheritance patterns with clarity and precision.

Dihybrid crosses continue to serve as both educational cornerstones and practical tools in genetic research, bridging classical theory with contemporary innovation.

Whether guiding a breeder through a selection series or helping clinicians interpret multi-gene risk profiles, the dihybrid cross stands as a testament to the enduring power of Mendelian principles in unlocking the secrets of heredity.

Related Post

Marion Sc’s Transformative Journey: From Mineral Frontier to Renewable Power Leader in Northern Territory

Converting Your Solid Fuel Stove To Oil: A Practical Guide for Smarter, Cleaner Burning

Mera Peer Jalali Hai: The Soulful Resonance of Qawwali Through Soulful Song & Lyrics

Heidi Kill Tony: The Unrelenting Journalist Who Turned Public Scandal into National Conversation