Limiting Reagent Unlocked: The Key to Mastering Chemical Limits in Synthesis

Limiting Reagent Unlocked: The Key to Mastering Chemical Limits in Synthesis

In the precise choreography of chemical reactions, the concept of a limiting reagent defines the boundary between triumph and waste—determining exactly how much product can be formed, no more, no less. Whether in laboratory research, industrial manufacturing, or educational settings, understanding this principle is foundational to controlling reaction outcomes, optimizing resource use, and driving innovation. Far more than a theoretical footnote, the limiting reagent stands as the cornerstone of stoichiometric accuracy, guiding chemists toward efficiency and reliability at the molecular level.

The definition of a limiting reagent is both simple and powerful: it is the reactant in a chemical equation that is entirely consumed before any other reactant reaches its theoretical maximum, thereby halting the progression of the reaction. “Once the limiting reagent is gone, the reaction stops,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a computational chemist at MIT’s Materials Science Laboratory.

“It’s the mole listener that sets the pace—no more product forms once it’s depleted.” Unlike excess reagents, which remain unneUsed but unused, the limiting reagent dictates the final yield with exact dimensional clarity, dictated by the mole ratio described by the balanced chemical equation. Consider a basic synthesis reaction: 2 moles of hydrogen gas react with 1 mole of oxygen gas to produce water (2H₂ + O₂ → 2H₂O). In this equation, hydrogen acts as the limiting reagent if only 3 moles are supplied while oxygen offers 1.5 moles—only enough to react with 3 moles of H₂, leaving O₂ in excess.

The 1.5 moles of O₂ remain unreacted; the 3 moles of H₂ are spent—the limiting reagent. This principle extends across all stoichiometric transformations, from pharmaceutical production to industrial catalysis.

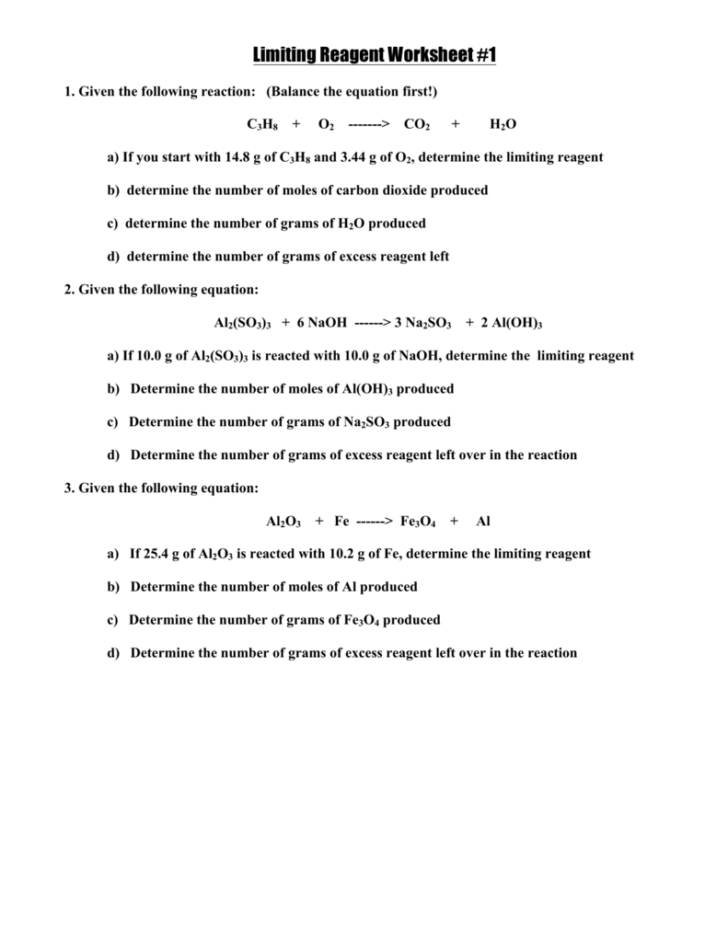

Identifying the limiting reagent demands careful calculation and precise data.

It begins with gathering the quantities of each reactant—typically expressed in grams or moles—and comparing those values to the mole-to-mole ratios required by the balanced equation. For example, if a reaction requires 1 mole of sodium (Na) per 2 moles of hydrochloric acid (HCl), then 10 grams of Na (molar mass 23 g/mol = 0.435 moles) and 50 grams of HCl (molar mass 36.5 g/mol = 1.37 moles) create a clear imbalance: Na runs out first (0.435 < 0.685 required), making it the limiting reagent. “Accuracy here directly impacts yield; even small measurement errors can shift whether a reaction succeeds or stalls,” notes Dr.

Rajiv Mehta, a chemical engineer at Bayer CropScience.

The methodology for identifying limiting reagents follows a structured sequence: first, convert all reactant masses to moles using molar masses; second, apply the stoichiometric coefficients from the balanced equation to determine theoretical consumption; third, compare mole consumption to available quantities—whichever reactant finishes first defines the limit. This process is repeatable across organic synthesis, inorganic chemistry, and biochemistry, proving essential regardless of reaction scale.

In pharmaceutical labs, where batch sizes range from milligrams to tons, controlling the limiting reagent ensures consistent drug formulations and minimizes costly overuse of expensive reagents like palladium catalysts or rare isotopes.

Beyond yield control, the limiting reagent concept plays a strategic role in scale-up and sustainability. Industrial chemists leverage it to optimize raw material procurement, reducing environmental impact by minimizing excess waste.

“Waste is not just messy—it’s economic and ecological. Identifying the limiting reagent means fewer byproducts, lower disposal costs, and cleaner processes,” argues Dr. Fatima Ndiaye, head of green chemistry initiatives at Novo Nordisk.

In a world committed to sustainable manufacturing, this precision aligns science with planetary responsibility.

Real-world applications underscore the reagent’s influence. In the synthesis of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) from salicylic acid and acetic anhydride, stoichiometry mandates a 1:1.2 mole ratio; deviations lead to incomplete conversion and impurities.

Similarly, in fuel synthesis, optimizing oxygen-to-hydrocarbon ratios as the limiting factor prevents incomplete combustion or excess unreacted components. Each example reinforces the limiting reagent as a silent architect of chemical efficiency.

Recognizing and manipulating limiting reagents transforms chemistry from an art into a predictive science.

It empowers researchers to design robust, scalable processes where every molecule counts. Mastery of this concept not only enhances experimental success but also drives innovation across energy, medicine, and materials. As laboratories push toward greener, smarter synthesis, the limiting reagent remains an immutable force—dictating outcomes with mathematical clarity and practical precision.

In the end, mastering the limiting reagent is more than a technical skill—it’s a mindset of precision and foresight. It teaches chemists to anticipate material constraints, respect stoichiometric truths, and engineer reactions with intention. This principle, embedded in every reaction setup, quietly shapes progress across modern chemistry—ensuring that every experiment, every batch, and every breakthrough reaches its full potential, limited only by intent, not oversight.

Related Post

10 Crucial Facts Before Subscribing to Piper Quinn’s OnlyFans Free Leak Content

Discover TV’s Goldfish: TV Guide’s Essential Guide to Life-Changing Shows

The Indomitable Force: How Another Word for Inevitable Shapes Every Aspect of Human Experience

Newark Arrest and Fatality Clarified: Metro Police Conduct Fatal Shooting Investigation on Broad Market Street