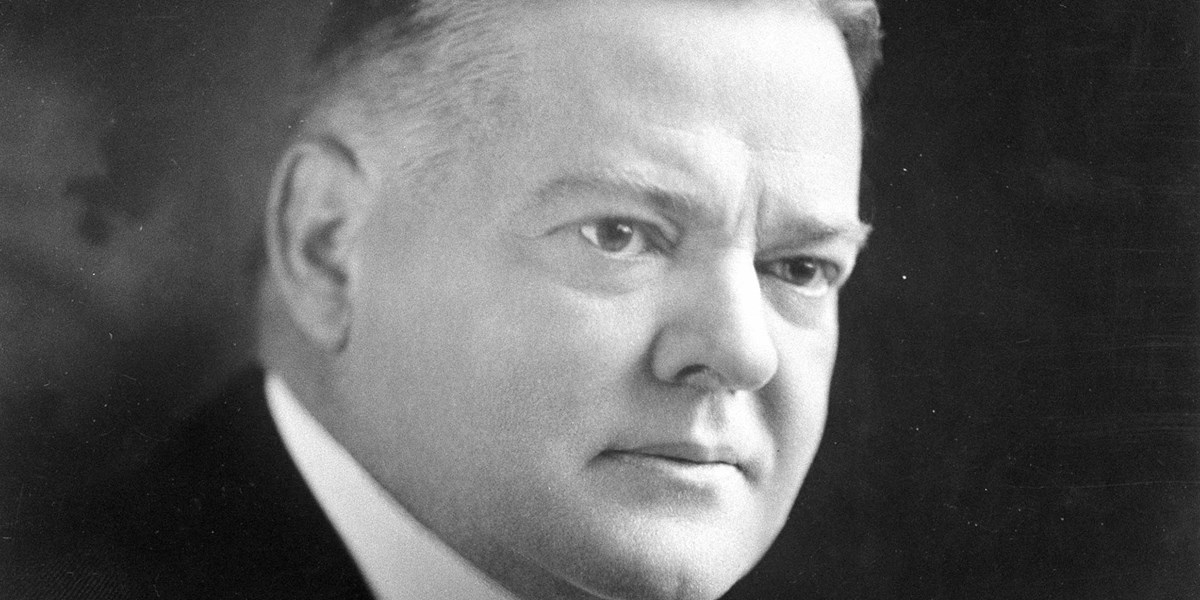

Herbert Hoover: The 31st U.S. President Who Defined an Era of Crisis

Herbert Hoover: The 31st U.S. President Who Defined an Era of Crisis

When Herbert Hoover assumed the presidency in 1929, the United States stood on the brink of profound upheaval—a moment that would define not only his legacy but also the trajectory of American politics. A man of immense technical expertise and reformist vision, Hoover approached the presidency as engineer and humanitarian before politics defined him. Yet, his tenure was dominated by the most violent economic shock the nation had faced: the Great Depression.

His leadership, shaped by belief in voluntarism and self-reliance, collided with the stark reality of mass unemployment and suffering, leaving historians to weigh his intentions against their outcomes. This article unpacks the complexity of Hoover’s presidency, revealing how his ideals and the unfolding crisis forged a presidency remembered as both principled and tragically out of step with the times.

Born on August 10, 1874, in West Branch, Iowa, Hoover’s early life laid the groundwork for a career marked by efficiency and duty.

An orphaned child raised in modest circumstances, he excelled at Stanford University’s engineering program, launching a professional path that led him to prominence in international mining ventures before he entered public service. Appointed Secretary of Commerce by Warren G. Harding in 1921, Hoover wielded the role as a platform to modernize American industry, promote technological innovation, and advocate for standardization—efforts that earned him respect but also exposed tensions between government intervention and free-market ideology.

When President Calvin Coolidge declined to seek a third term in 1928, Hoover faced the daunting task of succeeding a Republican era of prosperity, entering office amid soaring stock markets and widespread optimism—only to inherit a fragile economic foundation just months before it collapsed.

Entering Office: Promise, Optimism, and the Fragile Economy

Hoover took the oath of office amid an atmosphere of resilient confidence. In his inaugural address, he spoke of progress and shared responsibility, declaring: *"We are facing a setback, not disaster—a reversing of our fortunes to be met with renewed unity and effort."* This tone reflected his deep conviction that government should guide, not dominate, economic life.Unlike more activist predecessors, Hoover championed what he called “functional cooperation”—encouraging national organizations, businesses, and localities to voluntarily address depression’s early signs. He believed that inherited American virtues of industry and community would turn crisis into recovery. Yet beneath this confidence, financial vulnerabilities festered: overleveraged industries, declining agricultural prices, and an unstable banking system.

The autumn supply shocks, collapsing agricultural output, and corporate failures unrestrained the imbalance, setting the stage for disaster—one Hoover’s policies would scramble but ultimately fail to contain.

By 1930, the economic collapse deepened. Unemployment rose sharply, devastated industrial cities, and breadlines became a common sight in neighborhoods once emblematic of American abundance.

Hoover’s response centered on voluntarism, public-private partnerships, and limited federal aid. His "Voorhip Policy" urged industries to maintain wages, banks to stabilize credit, and communities to organize relief. Despite these efforts, critics—including economists, reformers, and soon-to-be-elected politicians— argued the approach was too passive, insufficient, and wedded to outdated notions of self-reliance.

Hoover personally toured relief centers, oversaw the establishment of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to inject liquidity into banks and railroads, and promoted public works projects, but the scale of suffering overwhelmed these measures. His refusal to enact broad federal unemployment relief crystallized public frustration.

Key Policies and Initiatives: Engineering Hope in a Time of Collapse

Hoover’s administration pursued a series of targeted interventions rooted in infrastructural investment and institutional cooperation: - The Federal Relief Unemployment Act of 1930 authorized federal funds for public works and local relief, though implementation remained decentralized.- The Bonus Army protests of 1932—veterans demanding early payment of service bonuses—exposed the limits of his restraint, culminating in a controversial military dispersal that damaged his reputation. - The Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929 sought to stabilize farm prices through cooperative marketing, aiming to help a sector hardest hit by falling demand. - The NRA’s precursor policies emphasized sector-wide fair wages and prices, though they lacked enforcement mechanisms Hoover deemed incompatible with voluntaryism.

Each effort reflected his belief in structured, technocratic solutions—not direct federal handouts—as the path to recovery.

Policy Philosophy: Volunteerism, Individualism, and the Limits of Pre-Depression Thinking At the core of Hoover’s presidency lay a philosophical commitment to what contemporaries called “rugged individualism.” He viewed government as a facilitator, not a savior, and saw voluntary cooperation as America’s strongest institutional asset. “No person or group is poor by hereditary privilege or by accident of birth,” he declared, “all are poor by judgment and failure.” This worldview guided his reluctance to adopt direct federal cash transfers or large-scale unemployment insurance—choices that became defining flaws when the crisis demanded bolder action.

Historians debate whether Hoover’s ideals were a courageous defense of American virtues or a profound misreading of systemic economic collapse. His trust in markets and skepticism of federal cradle-to-grave aid left him ill-equipped to address unemployment’s magnitude and persistence.

Detailed records reveal Hoover’s attempts to coordinate industry: requiring firms to maintain payrolls and profits, urging banks to avoid moratoriums on loans, and supporting technical experts in local recovery boards.

Yet these efforts were often fragmented, underfunded, and politically constrained. As economist Milton Friedman later observed in _Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money_, “Hoover’s refusal to embrace federal deficit spending akin to war mobilization signaled both his conviction and his impasse.” The president’s tactical focus on infrastructure—such as the Hoover Dam (named in his honor)—symbolized engineering promise but could not overcome the broader collapse of private demand and confidence.

Public Perception and Political Fallout

Early in his term, Hoover projected competence and calm—a sharp contrast to the shock of the crash.Newspapers praised his “quiet efficiency,” yet by year’s end public trust eroded. The Bonus Army’s 1932 confrontation in Washington, D.C., where cavalry charged demonstrators, remains a moral nadir, immortalized by Hamilton Fish’s quote: *“This was not a petition—it was a mob demanding charity.”* Media coverage, including harrowing photos by Dutch roughly, amplified national outrage. Hoover’s subsequent campaign victory in 1932 was decisively overcome by Franklin D.

Roosevelt’s promise of a “New Deal”—not just new policies, but a transformative governmental role in economic security. The election marked a turning point, casting Hoover’s presidency as a last gasp of pre-Depression governance, unable to adapt to an era of mass hardship.

Legacy: A Complex Portrait of Crisis and Leadership

Herbert Hoover’s presidency, though cut short by economic catastrophe, left enduring marks on American political thought.His commitment to federal infrastructure investment and cooperative federalism influenced future public works programs, while his failure to deploy robust federal relief underscored the need for more proactive crisis management. A man of immense skill, Hoover faced a crisis that redefined political expectations: citizens demanded not just good intentions, but tangible action. His belief in voluntaryism, once seen as principled, increasingly appeared outdated when confronted with systemic failure.

Today, historians assess Hoover not as a villain, but as a president caught between idealism and history’s unforgiving pace. His legacy encapsulates a pivotal moment: the collision between individualistic principles and collective suffering, between presidential restraint and public demand for relief. In the unforgiving light of the Great Depression, Hoover’s story endures—not as a cautionary tale alone, but as a study in leadership under extreme pressure, reminding us that even well-meaning governance must evolve with the challenges it confronts.

His presidency, often overshadowed by disaster, reveals the fragile balance between vision, values, and the unfolding demands of a nation in turmoil.

Related Post

Seal Fly Like An Eagle: Precision, Grace, and the Secret Typified in Nature’s Song

Angels vs Dodgers: Live Score Battle — Scores, Stats, and Real-Time Updates in the High-Octane Dodgers-Al Alla Game

Understanding Serfdom: Unveiling the Hidden Machinery of Medieval-Like Servitude

A Closer Look at Neil Flynn’s Personal Life: The Legacy of Discovering His Son T, Family Ties, and Enduring Legacy