Fick’s Law of Diffusion: The Silent Engine Behind Life’s Transport Systems

Fick’s Law of Diffusion: The Silent Engine Behind Life’s Transport Systems

< adviser>In the intricate choreography of biological, chemical, and physical processes, the movement of molecules across barriers defines function as much as structure. At the heart of this invisible motion lies Fick’s Law of Diffusion—a foundational principle that quantifies how substances disperse through materials, from cellular membranes to industrial membranes. Governed by simple yet powerful mathematics, Fick’s Law reveals the rules by which gases, nutrients, drugs, and even pollutants traverse space, setting limits and enabling advancements across science and engineering.

Fick’s Law, formulated in the early 20th century by German physiologist Adolf Fick, remains a cornerstone of transport phenomena.

It describes diffusion not as random drift, but as a directional flux driven by concentration gradients—molecules naturally migrating from regions of high concentration to low concentration. Today, this law underpins disciplines ranging from pharmacology to environmental science, enabling predictions in everything from drug delivery systems to air filtration technologies.

Understanding the Mathematics: How Fick’s Law Quantifies Diffusion

Fick’s first law expresses diffusion flux—molecules moving per unit area per time—as proportional to the negative gradient of concentration. Mathematically,

J = –D (dC/dx)

where J is the diffusion flux (amount of substance per area per time), D is the diffusion coefficient (a material-specific constant), and dC/dx is the concentration gradient across a unit distance.

The negative sign indicates diffusion flows from high to low concentration, emphasizing the unidirectional nature of this process.

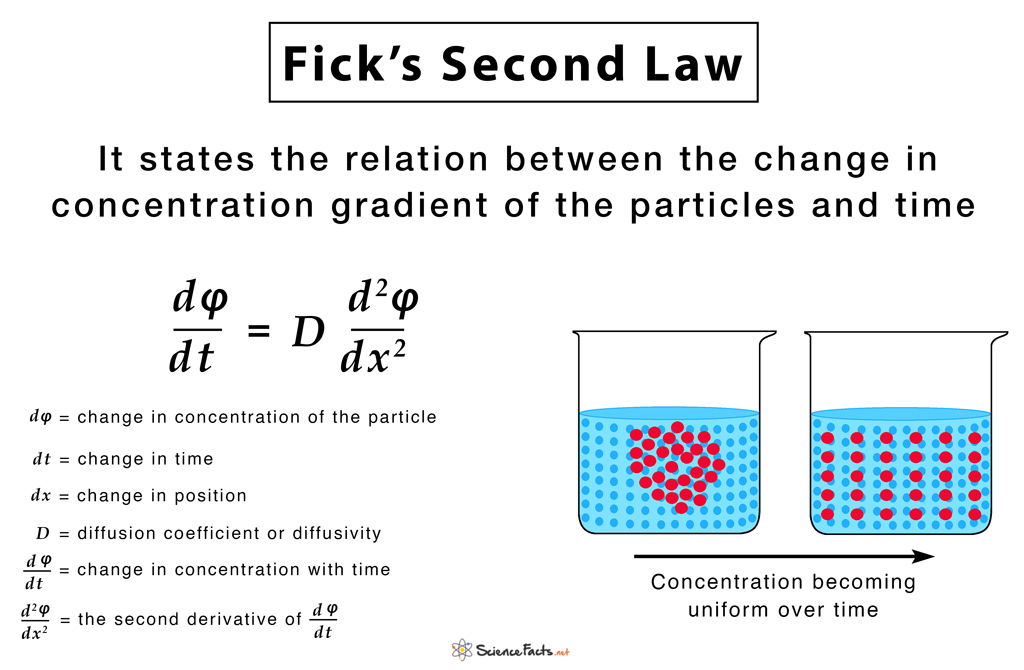

For steady-state diffusion—where conditions don’t change over time—Fick’s second law extends this model, incorporating time dependence through the diffusion equation: ∂C/∂t = D ∂²C/∂x². This equation reveals how concentration changes in space over time, allowing scientists to simulate and predict how substances spread in solids, liquids, and even dynamic biological environments.

Key Factors Influencing Diffusion Rates

Diffusion is not a uniform process; its speed and efficiency depend on several critical variables:

- Diffusion Coefficient (D): A material’s intrinsic ability to transport molecules. Smaller, lipid-soluble molecules like oxygen diffuse rapidly through cell membranes (~2 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s in phospholipid bilayers), while large proteins may require specialized channels or vesicles.

- Concentration Gradient: Sharper gradients drive faster diffusion.

A strong difference in solute concentration across a barrier accelerates flux more than a gentle slope—directly amplifying J in Fick’s first law.

- Temperature: Higher thermal energy increases molecular motion, boosting D. For instance, diffusion rates roughly double for every 10°C increase in temperature.

- Barrier Thickness and Structure: Thinner, porous materials enhance diffusion. A membrane just 0.1 μm thick can permit vastly greater flux than a dense polymer sheet.

These variables are interdependent and often optimized in natural and engineered systems.

In biological systems, for example, alveolar membranes in lungs are ultra-thin and highly permeable to sustain efficient gas exchange—grounded in Fickian principles.

Real-World Applications: From Cells to Industry

Fick’s Law transcends theory—it powers innovation across sectors:

In inhalers and oral forms, Fick’s Law helps design dosage regimens based on molecular size, membrane permeability, and desired absorption rates.

Case Study: Oxygen Diffusion in Human Respiratory Systems

In human lungs, oxygen diffusion exemplifies Fickian behavior.

Alveolar air contains 160 mmHg of O₂, while pulmonary capillary blood holds only ~40 mmHg. This 120 mmHg gradient drives O₂ flux across the thin alveolar membrane (~0.2 μm thick) with a diffusion coefficient of ~0.25 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s. Using Fick’s Law: J = – (0.25 × 10⁻⁹) × (120 / 0.0002) ≈ 1.5 × 10⁻⁵ mol/(

Related Post

Unveiling The Life And Journey Of Sasha Nugent: From Rising Star To Cultural Recent Icon

Altitude For Denver: Defying the Skyline with Unmatched Wellness Prospect

When You Love Someone Lyrics: The Unspoken Language of Heart and Soul

One All Above: The AHP Framework Revolutionizing Strategic Decision-Making Across Industries