Electron Geometry vs. Molecular Geometry: The Shape That Shapes Reactivity and Function

Electron Geometry vs. Molecular Geometry: The Shape That Shapes Reactivity and Function

Understanding molecular and atomic structure hinges on geometry—specifically, how electron pairs arrange themselves in space around a central atom. Electron Geometry and Molecular Geometry represent two complementary frameworks that decode these spatial relationships, each revealing distinct insights into molecular behavior. While both rely on the Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory, their focus diverges: one describes electron pair repulsion at the core, while the other describes the actual shape of atoms bonded to a central atom.

Grasping their differences is essential for interpreting chemical reactivity, physical properties, and even industrial applications of compounds.

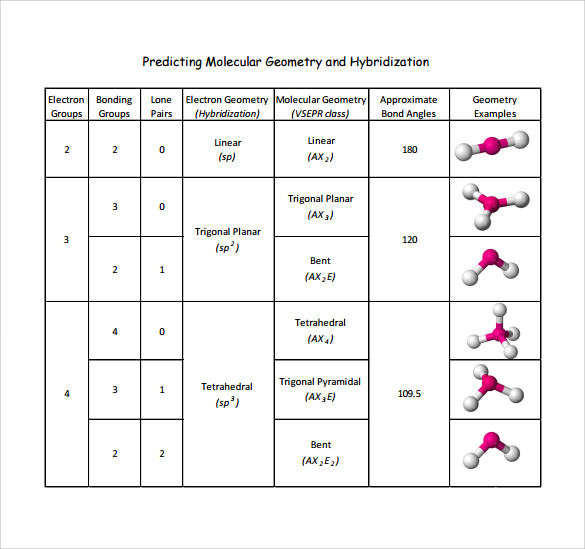

At the heart of both concepts lies VSEPR theory, which asserts that electron pairs—both bonding and non-bonding—repel each other and adopt configurations that minimize repulsion. This foundational principle governs the expected electron geometry, while the molecular geometry accounts for visible atoms, factoring in lone pairs that distort bond angles.

For instance, methane (CH4) exhibits tetrahedral electron geometry and molecular geometry, with electron pairs evenly spaced at 109.5°, resulting in predictable symmetry.

Electron Geometry: The Theoretical Blueprint of Electron Pair Arrangement

Electron Geometry defines the three-dimensional spatial configuration of all electron pairs—bonding and non-bonding—around a central atom, treating lone and bond pairs as repulsive entities. It establishes the idealized angle and shape that dictate how electrons distribute to minimize repulsion, serving as the blueprint for bonding arrangements. Unlike molecular geometry, electron geometry encompasses all valence electrons, regardless of whether they participate in bonds or remain as lone pairs.This broader view is critical for understanding molecular stability and reactivity from the electron perspective.

VSEPR theory categorizes electron geometries based on crystALLine arrangements: - Linear: Two electron pairs spaced 180°, as in CO2 - Trigonal Planar: Three pairs at 120°, exemplified by BF3 - Tetrahedral: Four pairs at 109.5°, characteristic of methane - Trigonal Bipyramidal: Five positions with axial and equatorial angles (90° and 120°) - Octahedral: Six pairs arranged with 90° angles, seen in IF6 “Electron geometry is not just a visualization tool—it predicts molecular polarity, reactivity, and even phase behavior by revealing the repulsive forces shaping atomic arrangement,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, a physical chemist specializing in molecular structure modeling.

Key features include: - All electron pairs repel each other equally, regardless of bond type - Lone pairs occupy more space than bonding pairs, pushing bond angles inward (e.g., H2O’s bent shape at ~104.5°, versus tetrahedral 109.5°) - The geometry determines electron density distribution, influencing intermolecular forces and chemical behavior

While electron geometry provides a pure structural map, Molecular Geometry zooms in on the actual atomic layout—the visible skeleton of the molecule. It reflects only the positions of bonded atoms, offering a clearer picture of how molecules interact, bind, and function in real-world conditions. Electron pairs that do not participate in bonding—lone pairs—are physically invisible but critically shape molecular shape and polarity.

Molecular Geometry: The Actual Form That Dictates Chemical Behavior

Molecular Geometry describes the three-dimensional arrangement of only the atoms bonded to a central atom, derived by mapping the positions of bonded atoms while accounting for lone pairs that influence spatial orientation. Unlike electron geometry, it ignores non-bonding electrons, focusing on how visible atoms cluster based on VSEPR repulsion among bonding pairs. This distinction is crucial: lone pairs compress bond angles but disappear from the molecular shape, making molecular geometry the real-life interface between molecules and their environment.Still governed by VSEPR, molecular geometry takes the simplified model of active atoms and applies angular constraints: - Linear: AB (e.g., CO2), 180° bond angle - Bent (Angular): AX2E (e.g., H2O), lone pairs introduce angles below 109.5° - Trigonal Planar: AX3 (e.g., BF3), 120° - Trigonal Bipyramidal: AX5 (e.g., PCl5), axial-equatorial 90° and 120° distances - Octahedral: AX6 (e.g., SF6), 90° and 180° “The molecular geometry of a water molecule defines its ability to form hydrogen bonds—critical for life,” explains Dr. Raj Patel, a computational chemist. “Lone pairs on oxygen bend the structure into a bent form, creating a polar interface with unique solvation properties.”

Key characteristics include: - Bond angles directly reflect VSEPR repulsion; deviations reveal electronic effects - Lone pairs distort geometry (e.g., NH3’s trigonal pyramidal shape) but remain unseen - The molecular shape determines reactivity, dipole moments, and intermolecular interactions

Understanding these geometries reveals how invisible electron forces translate into visible molecular function.

Electron geometry maps pushback—how pairs repel to define potential—and molecular geometry delivers—how atoms align to create real, interactive forms. Both are indispensable: electron geometry lays the groundwork of repulsion, while molecular geometry delivers the operational shape. Together, they form the foundation for predicting molecular behavior across chemistry, pharmacology, and materials science, proving that shape is not merely aesthetic—it is functional, fundamental, and far far from accidental.

Related Post

Unpacking the Enigmatic Lyrics of Ozzy Osbourne’s “Perry Mason”: A Mystery Unwound

Mastering Financial Flexibility in Playmyworld: How Online Gaming Reshapes Real-World Money Management

Who Invented The First Car? The Revolutionary Surge That Changed Human Mobility

Unlock Every Secret: Master Murder Mystery 2 with the Ultimate Mm2 Exploits Guide