A Comprehensive Guide To Facet Hypertrophy: Definition And Causes

A Comprehensive Guide To Facet Hypertrophy: Definition And Causes

Facet hypertrophy is a skeletal phenomenon marked by the abnormal thickening of the articular facet joints in the spine—structures critical to movement, stability, and load-bearing. While often mistaken for pathological joint degeneration, this process represents a benign but clinically significant morphological adaptation. Far more than a passive change, facet hypertrophy reflects the spine’s dynamic response to mechanical stress and redistributes forces across vertebral segments to preserve structural integrity.

Recognizing both its precise definition and underlying causative mechanisms is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management in clinical practice.

At its core, facet hypertrophy refers to the abnormal enlargement of the hyaline cartilage-covered articular facets on each vertebra, most commonly affecting the cervical and lumbar spine. These facets, also known as zygapophysial joints, guide motion and limit excessive rotation and flexion.

Normally, their cartilage remains uniform and resilient, enabling smooth articulation. However, when subject to chronic stress, these joints undergo structural remodeling characterized by increased cartilage thickness and sometimes subchondral bone expansion. “This thickening is not a sign of disease per se, but a structural attempt by the body to absorb and distribute repetitive mechanical loads,” explains Dr.

Maria Chen, an orthopedic spine specialist. “It’s a compensatory adaptation rather than degeneration—though in some clinical contexts, it may coexist with wear-and-tear changes.”

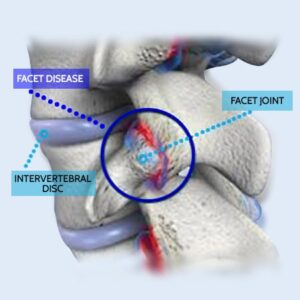

Anatomical Foundation: Understanding the Facet Joints

The human spine is a biomechanical marvel, composed of vertebrae layered over one another, each joined by paired facet joints positioned at right angles to permit movement while maintaining alignment. Each facet joint consists of two articular surfaces covered by hyaline cartilage, connected by a fibrous posterior ligament ligamentum flavum and anteriorly by a transverse ligament.These joints play a pivotal role in controlling motion: they restrict motion in specific planes, absorb shock, and transfer axial forces between vertebrae. When hypertrophy occurs, the cartilage expands outward, thickening the joint surface. This morphological shift alters joint biomechanics by redistributing contact pressures, potentially reducing shear forces but increasing compressive stress on the underlying bone and cartilage.

Key Triggers and Causes Behind Facet Hypertrophy

Facet hypertrophy rarely occurs in isolation; it typically arises from a confluence of mechanical, physiological, and environmental stressors. The primary drivers include chronic mechanical overload, postural imbalance, trauma, and degenerative processes—each influencing joint remodeling in distinct ways.Chronic mechanical overload is among the most prevalent causes.

Repetitive spinal loading—common in occupations requiring heavy lifting, prolonged standing, or sustained malalignment—initiates microtrauma to the facet joints. Over time, the articulatory cartilage thickens in response to increased stress, attempting to stabilize the joint. Modern lifestyles, with rising rates of sedentary behavior punctuated by vigorous activity, may exacerbate such strain.

“Poor posture—especially forward head positioning from screen use—creates persistent shear forces that overload the cervical facet joints,” notes Dr. Chen. Such habitual misalignment leads to uneven distribution of loads across the vertebral column, targeting specific facets for hypertrophy.

Trauma, both acute and cumulative, represents another significant catalyst. Cervical or lumbar disc injuries, whiplash events, or repeated compressive forces from falls can initiate inflammatory cascades within the joint. This inflammation stimulates chondrocyte activity—the cells responsible for cartilage maintenance—causing hypertrophic responses.

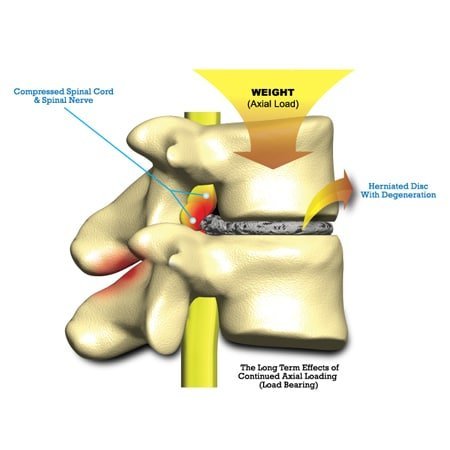

Unlike osteoarthritis, which includes cartilage breakdown, facet hypertrophy involves cartilage thickening without immediate erosion, preserving joint space initially but potentially altering motion dynamics. The degenerative spectrum also contributes, especially in aging populations. As the intervertebral discs lose hydration and height with age, facet joints bear greater load, accelerating remodeling.

“The body’s reaction to diminished cushioning is a protective thickening of joint surfaces,” says spine researcher Dr. Elias Torres. “It’s a remodel—not destruction—meant to compensate but which may also diminish normal mobility.” h3>Other Contributing Factors Beyond mechanical stress and trauma, several systemic and individual factors influence facet hypertrophy progression.

Age is a well-documented risk factor, with prevalence increasing markedly after the age of 40. Genetic predisposition also plays a role; variations in cartilage metabolism-related genes can affect susceptibility to joint thickening. Hormonal imbalances, particularly in menopause, may alter collagen synthesis and cartilage integrity, increasing vulnerability.

metabolic syndromes and inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis can indirectly contribute by altering joint biomechanics and local inflammation, fostering hypertrophic responses. Lifestyle elements further modulate risk. Smoking, for instance, impairs circulation to cartilage tissues, reducing nutrient supply and waste removal—critical for maintaining joint health.

Obesity amplifies mechanical load, particularly in weight-bearing spinal regions, thereby accelerating joint remodeling. Sedentary behavior weakens core musculature, diminishing natural spinal stabilization and increasing facet joint reliance during movement.

Clinical Relevance and Implications

While facet hypertrophy itself rarely causes immediate symptoms, its presence often signals underlying biomechanical disruption.Patients may experience mild stiffness, reduced range of motion, or localized pain—especially with hyperflexion or rotational movements—that mimics degenerative conditions. Importantly, hypertrophy frequently coexists with disc degeneration, spinal stenosis, or facet joint osteoarthritis, complicating diagnosis. Advanced imaging, particularly MRI and CT scans, reveals characteristic thickening of joint cartilage and possible subchondral bone changes, helping clinicians distinguish it from other pathologies.

“Clinicians must appreciate facet hypertrophy as a structural adaptation, not just a degenerative mark,” cautions Dr. Torres. “Misinterpreting it as irreversible degeneration risks overtreatment.

Instead, understanding its compensatory role guides targeted, conservative management—exercises to restore alignment, physical therapy, and stress reduction.” Recognizing prevalent contributing factors—such as poor posture or occupational strain—also enables preventive strategies, reducing long-term risk. In summary, facet hypertrophy represents a nuanced spinal adaptation driven by mechanical overload, injury, aging, and lifestyle forces. Its precise definition centers on cartilage thickening as a compensatory stabilization mechanism, not alone cartilage breakdown.

The causes are multifactorial, rooted in lifestyle, trauma, systemic health, and biomechanical imbalance. By dissecting these elements, clinicians gain critical insight to differentiate hypertrophy from pathology and tailor care accordingly—transforming a structural observation into a meaningful pathway for patient-centered diagnosis and management.

Related Post

Global Shifts Under Scrutiny: From War Flames to Climate Frontiers in the Daily News Pulse

Alyssa Donovan: TV Stardom, Birth, and Stature – The Rise of a Generation’s Favorite Face

Is It A Bank Holiday In India Today? Understanding the Nation’s Financial Lifecycle

Khloe Kardashian’s Royce Moment: A Lease That Launches a Legacy of Luxury